The principal dancer

Overwhelming talent and an irrepressible will enabled Misty Copeland to break new ground as the first Afro-American principal dancer of the famous American Ballet Theatre.

Aaron Hicklin (copy) & Michael Williams, Henry Leuwyler/Getty Images (photo)

Misty Copeland, 35

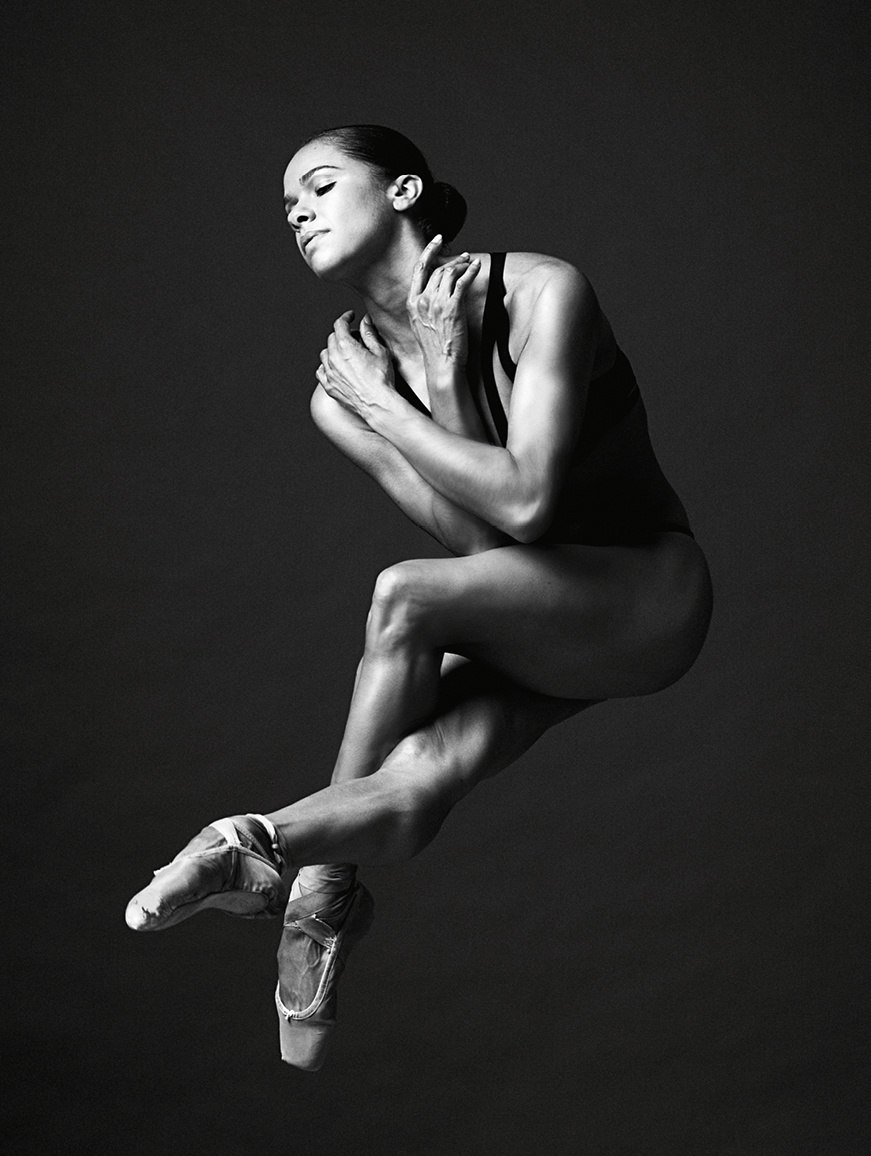

The first Afro-American principal dancer in the history of the acclaimed American Ballet Theatre, Copeland was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and raised in impoverished circumstances in San Pedro, California, where she shared a room with five siblings. Being named to Time’s list of the world’s 100 most influential people and gracing the magazine’s cover shot her to instant fame far beyond the ballet world. A popular ad campaign for the US sportswear brand Under Armour added to her celebrity. Recently, Estée Lauder named her as the face of the new perfume Modern Muse.

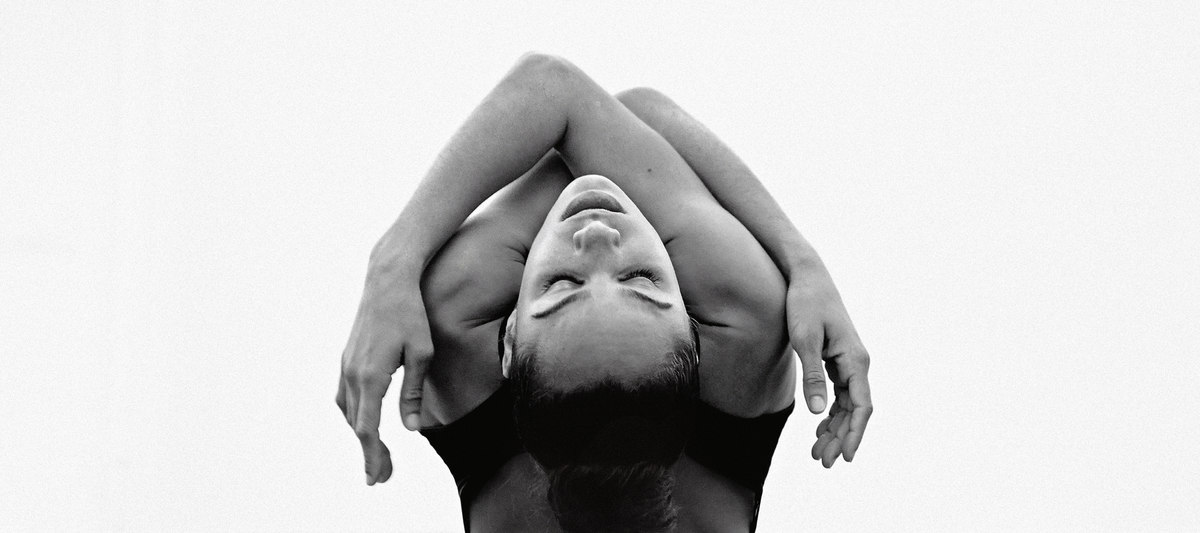

How does a poor, black American girl become the most famous ballerina of her generation? For Misty Copeland, principal dancer of the prestigious American Ballet Theatre, and the first black woman to achieve the distinction in the theater’s 75-year history, the answer is simple: You don’t give up. To overcome hardship and prejudice you persevere. You dance until you get better. And then you dance some more.

Growing up in the southern California town of San Pedro, Copeland had little exposure to ballet before crossing paths with Cindy Bradley, a dance teacher who gave lessons at the local Boys & Girls Club. That meeting was a kind of alchemy, according to Bradley, who can still recall the first time Copeland attended her class, shyly observing the other children at first, and then drawn inexorably to take her first steps. “I touched her foot and that’s when the magic happened,” Bradley recalls. “I knew she was special. She hadn’t danced before! It was an angels singing moment!” For Copeland, stepping onto the warped boards of the gymnasium was a moment of transformation. “I was, like, ‘Oh, I belong here,’” she recalls. “It was the first time I ever felt beautiful—just to look in the mirror and to be told, ‘You’re what a ballerina looks like.’”

On the dance floor Copeland felt free as never before—certainly freer than in her crowded home with five siblings, and a frequently tired and harassed mother, to make space for. At one point she recalls moving into an apartment owned by her mother’s boyfriend. The six children slept in the living room. For privacy she hid in the closet, often for long stretches at a time. “It wasn’t some fancy walk-in closet,” she says, lest anyone have the wrong idea. “I would sit in there, listen to music and play cards by myself.” Later they lived in a motel room where Copeland had to be extra creative to practice her dance. “I would be in the bathroom or I would step outside our door, and I would experiment, stretching and going through what I could remember from ballet class.”

For millions of Americans, Copeland’s Cinderella journey from deprivation and loneliness to the pinnacle of her profession is an archetypal story of triumph over adversity. At the Boys & Girls Club, today’s visitor is confronted with a painting showing Copeland in a forlorn crouch, forehead resting on her knees. Around her swirl words like agony, hurting, desolation, hardship and rejection—adjectives to describe her long journey to acclaim. Alongside is another painting in which Copeland pirouettes like a music box ballerina, liberated, while music notes spiral around her head. Nearby, a sign proclaims: “Great Futures Start Here.” Copeland is the poster child for those hopeful futures, the girl from the wrong side of the tracks who got to stand tall—on pointe shoes. “I’m often asked if I’m OK being referred to as the black ballerina,” she says. “And I say, ‘I don’t think that’s something I want to change.’ We’re still at a point where it needs to be acknowledged all the time.”

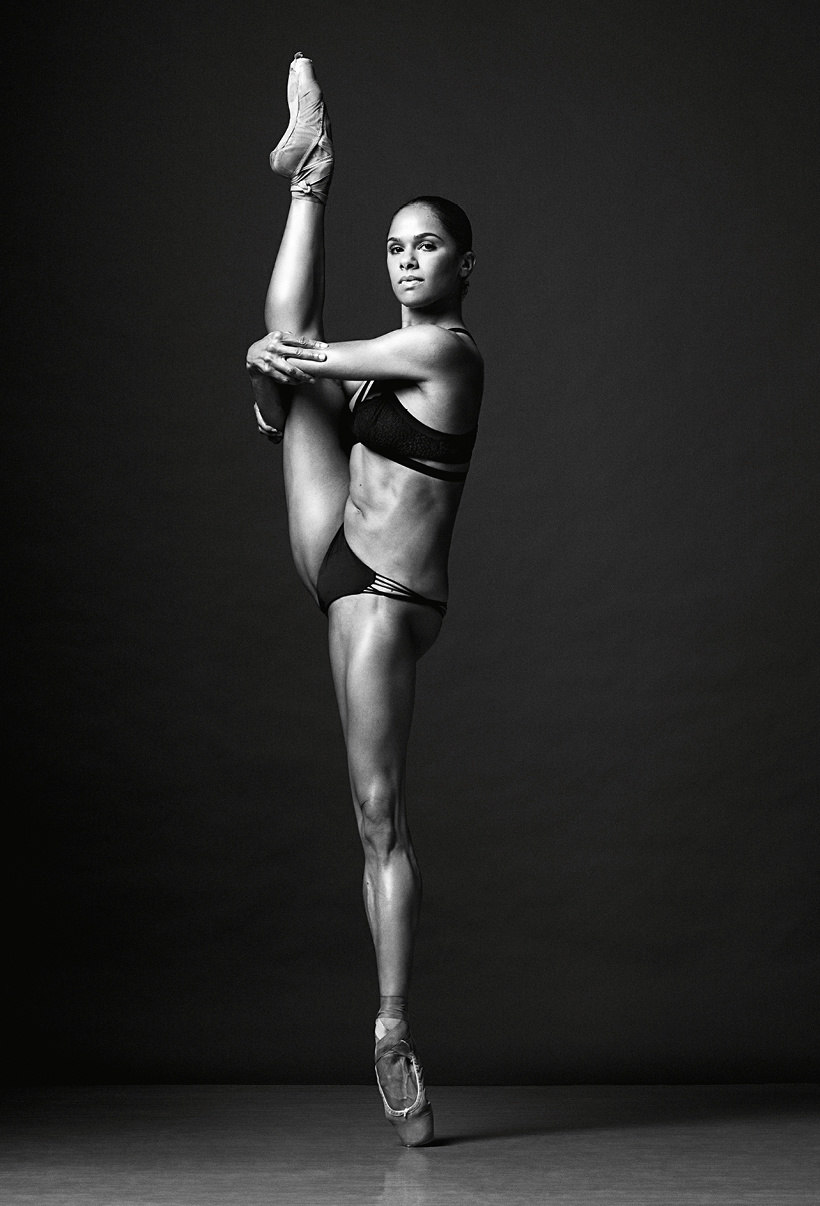

“Principal dancer” is the highest rank that can be attained in a ballet company. The leading roles, which call for stellar talent, are reserved for these artists. Misty Copeland became principal dancer in 2015, when she was 32—a relatively advanced age for this position.

It was the first time I ever felt beautiful.

Founded in 1939, the New York-based American Ballet Theatre (ABT) ranks among the top three ballet companies in the US. Its ensemble performs the great classics such as Swan Lake as well as modern pieces at the renowned Metropolitan Opera House.

But Copeland’s story speaks to everyone, black and white, male and female, because it’s also a story of pursuing a passion no matter the obstacles thrown in your way. Copeland was 13 before she took her first dance steps, far older than most ballet dancers, but her dedication took her all the way to the American Ballet Theatre where she was made principal dancer in 2015. She might have got there sooner but for another major setback in 2012. Shortly after debuting in the title role of Stravinksy’s 'Firebird', Copeland discovered six stress fractures in her tibia. It would take seven months of physical therapy before she could return to the stage. Others in her place might have been dissuaded, but Copeland, unwilling to stop working, sought out a rare technique in which she rehearsed on her back. Known as floor bar, the method allows dancers to do almost everything they would do standing up, but without applying any pressure to the feet and legs. “Gravity is gravity,” says Copeland. “Lying on your back helps you work evenly and correctly.” Like Victoria Page in the movie 'The Red Shoes', it seems that Copeland is able to endure anything so long as she is able keep dancing. In many ways, the obstacles have given her strength. “It’s tough to be successful in the ballet world,” she says. “It takes a strong and resilient person, and I feel because of the way I grew up I’m much more prepared than a lot of girls who came from privilege and money."

Last year Copeland was able to reprise her 'Firebird' role again, fully recovered and stronger than ever. In the intervening period she also found time to write a memoir, interview President Obama and launch a line of clothing for ballerinas who do not fit the stereotypical mold—meaning unnaturally thin. “I wanted to create something that could work for every woman’s body and still be elegant,” she says. “There were times when I was bigger and going through puberty and I was just embarrassed to be in the studio and have something that didn’t fit me properly.”

It’s tough to be successful in the ballet world.

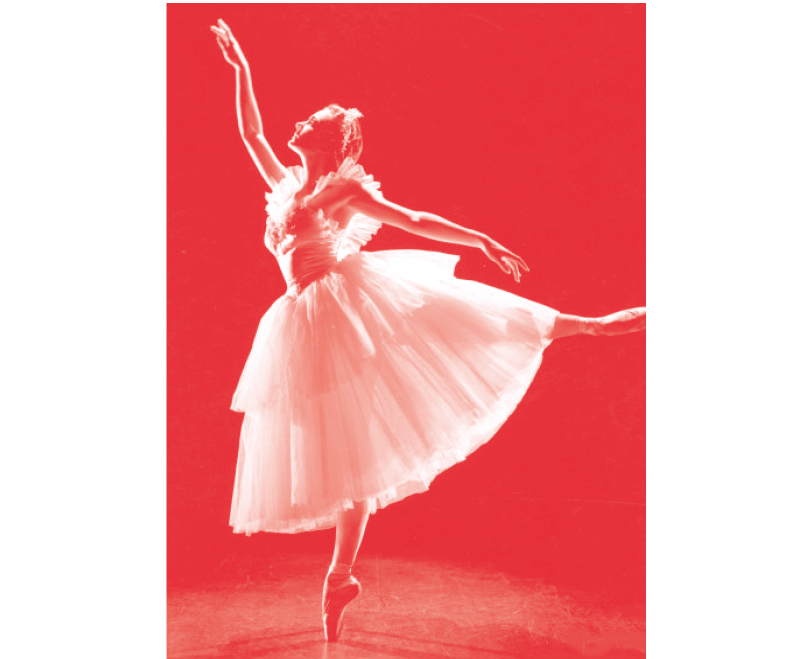

Misty Copeland performed her first title role at the ABT in 2012, dazzling audiences and critics alike in Igor Stravinsky’s 'Firebird'. She reprised this, her signature role, in 2016, thrilling ballet fans yet again.

At the end of December 2015, Misty Copeland returned to her old home town of San Pedro for a special ceremony at which the city mayor unveiled a plaque renaming an intersection of 13th Street and Pacific Avenue, outside Cindy Bradley’s dance school, “Misty Copeland Square.” Children crowded the sidewalk to catch a glimpse of their hero. Los Angeles councilman Joe Buscaino paid homage to the fortitude with which she had dealt with poverty, racism and injury in her path to becoming America’s best-known dancer. A tearful Cindy Bradley told the assembled crowd of “the beautiful quiet little girl with so much heart” who had become a member of her family. Copeland in turn thanked Cindy and her husband and son for “making me into the woman that I am, for introducing me to ballet, and for giving me a path and platform to change not only my life, but so many little brown girls’ lives.”

For Bradley, this is the ultimate reward of all that faith and belief and hard work. “Misty has changed the game of ballet—she has forced diversity,” she says. “You should see the hunger for ballet that the kids in these neighborhoods have. Before, they didn’t have any idea what it was. Misty hadn’t been exposed to it.” She blinks back tears of pride. “It’s huge what she’s done—it’s saved ballet.”

Further photo credits: Wikimedia Commons, Jesse Orrico/Unsplash, Jan Schuenke/PLATNUM, Anthony Delanoix/Unsplash, Siegfried Layda/Getty Images, Library Of Congress