The new beat

A city reinvents itself. As it rises from its ruins, the power of local initiatives is exerting a magnetic pull on the creative class in the U.S. Detroit was always tougher, more challenging and wilder than other places. We take a trip to a city full of hope. And to the roots of techno.

Sabine Cole and Jan Schlüter (copy) & David Fischer (photo) & Simon Roloff (video) & Juan Atkins (music)

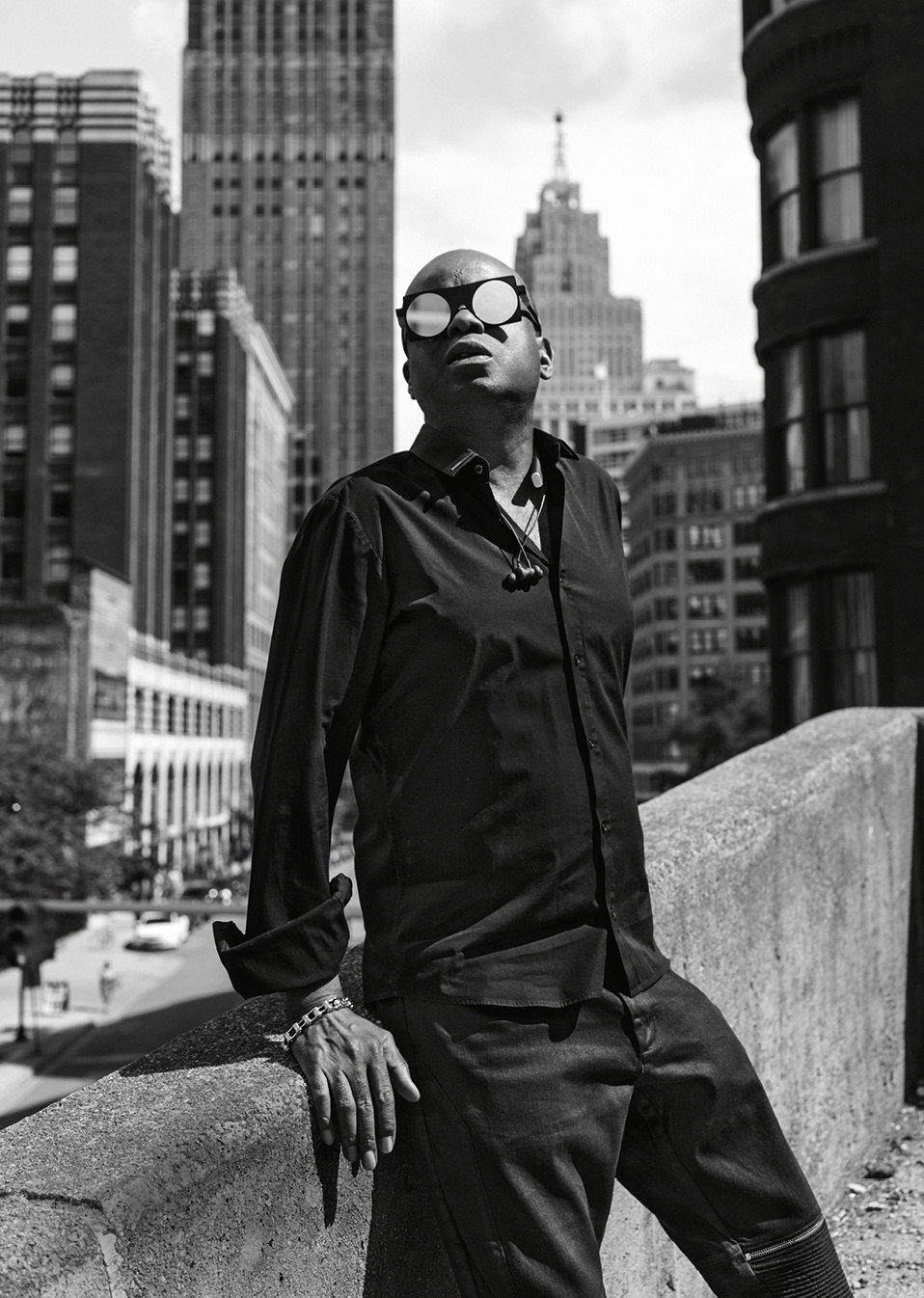

Juan Atkins,

“the originator of techno”

“Detroit has always produced groundbreaking music. Maybe it has something to do with its special geographical location or the fact that the city is built on the site of Native American battlefields. One thing is for sure: Detroit was predestined for creativity.”

“If you come to make a contribution, if you respect us, if you want to move into the neighborhood and live among us, we’ll welcome you with open arms. If you just want to get rich or check things out, you should stay away.” It’s a statement that undoubtedly rings true for all Detroiters. We follow Mose Primus, aka Ambassador Mose, through Yorkshire Woods. It doesn’t take much to imagine how the brick houses were once neat and inviting. “This used to be a vibrant neighborhood. Then people lost their jobs and homes. The 2007 financial crisis did the rest. A couple of years ago, we decided to take matters into our own hands. Demolish derelict structures. And mow the lawns everywhere—even at the abandoned houses. We want to buy and refurbish the former school. We’re going to play baseball on the field again.” But first, a community space is to be created where people from the neighborhood can meet and talk. Mose and his fellow campaigners are backed by Detroit Future City, a foundation that defines itself as both a think tank and strategic nonprofit organization that plays a decisive role in revitalizing the city. Responsible for one of the seven districts, Pier Amelia Davis is Land Use & Sustainability Coordinator, a role which involves ensuring that local projects receive technical equipment and financial support. Projects must apply for funding on their own initiative. This is to prevent a top-down approach and instead only subsidize initiatives that the communities themselves have chosen and planned. Pier is a fairly recent college graduate who joined Detroit Future City half a year ago. A native of Michigan, she deliberately chose to move to Detroit. “This place gives me the chance to create something. And make a difference.” It’s a sentiment that we’ll hear again and again. Young, educated people who have plenty of options but feel the need to bring about change as well are discovering Detroit for themselves.

Terrence West is Marketing and Communications Manager at the Michigan Science Center. When we meet him in Artist Village Detroit, he prefers to speak in his personal capacity. That’s because Terrence grew up precisely where Detroit was—and still is—hurting. One of a family of nine children growing up in Old Redford, he had to fight for survival—there’s no other way of putting it. Terrence shows us his favorite piece of graffiti. A boy sits at the top of a beam, close to the sky. He’s up there because a group of children below weigh down the beam like a seesaw. Terrence loves the analogy behind the image: “My hood ensured that I moved up.” The others stuck it out here, supporting me, so that I could leave. I’m the boy at the top of the beam.” Seeing what was possible and how it could be achieved, he seized his chance. “The kids here don’t have any positive role models. How should they know what it means to work when there’s nobody around with a job to show them how it’s done? How can they know what a really great steak sandwich tastes like when they’ve never had one? You have to get out of here and overcome the stifling limitations to discover what it is that’s worth fighting for.”

Juan Atkins on a Downtown parking deck at the Detroit Institute of Music Education, where he used to teach. The mirrored sunglasses are a signature look among all Deep Space Radio artists.

The People Mover is a train that circles Detroit’s Downtown neighborhood. Until a few years ago, it offered a bleak view of abandoned properties and dilapidation. Today, the vistas reveal vibrant streets and cafés, revitalization and construction everywhere.

Pier Amelia Davis is known to neighbors in Yorkshire Woods for “her strong commitment to serving the community”—a quality not all the area’s young residents are noted for.

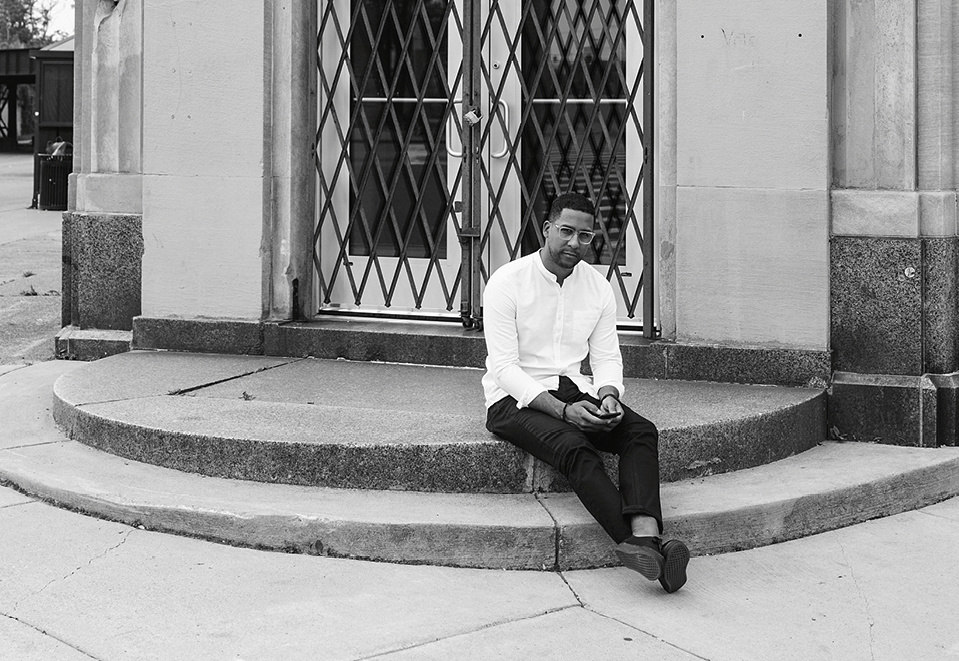

Julio Cedano is new in town. He belongs to the “creative class” just discovering Detroit. The art space Grand On River, a former bank, is a good example of the innovative capacities of the young artists the city attracts.

Terrence West also gives back some of the solidarity he has experienced. His efforts include helping people whose gas has been turned off or who face the prospect of homelessness, and connecting them with the Heat & Warmth Fund for Michigan residents. Terrence accepts the responsibility he bears as a role model in his community.

Label manager Dimitri Hegemann wants to give back to Detroit, too; after all, the majority of Tresor Records artists are natives of the city. He partnered with his old friends Jeff Mills and Mike Banks of the Detroit techno label Underground Resistance to set up the nonprofit Detroit-Berlin Connection.

When we ask to take Chazz Miller’s picture, he leads us down a small alley bordering Artist Village Detroit. A successful artist, he also puts his weight behind the neighborhood project. He decorated the walls in this alley that’s just around the corner from his studio with graffiti immortalizing the kings of Motown: Michael Jackson and Prince. Poverty is ubiquitous in Detroit. But so is music, the people’s pride and joy. Before saying goodbye, we ask him if he listens to techno—the music that was invented when Motown could no longer offer anything new. He smiles broadly. “Of course. But here we listen to ghettotech.” He explains that the dance moves just look better. Despite—or perhaps because of—the economic hardship, Detroit’s creative spirit keeps on generating innovations, especially in the music department. The key contributor to the present renaissance is arguably the birth of techno. Techno is black. “Black music from Motown, Detroit.” Its source can be indisputably traced back 35 years to one man, who today is credited as its originator: Juan Atkins.

We meet Juan at a Downtown café that is the temporary home of a small Internet radio station simply named after Detroit’s area code: 313.FM. Dedicated exclusively to electronic music—chiefly techno in all its iterations—the little station’s lineup of international star DJs on this weekend is impressive. The Movement Festival attracts scores of techno fans from across America and abroad. And sets the entire city throbbing. Juan Atkins greets local radio-show host and DJ Brent Scudder, who responds with a casual nod. In Europe, Juan Atkins would be a celebrity and VIP to be approached with nothing short of awe. “Here, you meet the stars in the 7-Eleven around the corner. It’s a pretty small scene in Detroit,” explains Brent, who, like Juan, was born and bred in the city. We settle into the small, secret techno club located in the basement of Urban Bean Co., a coffee house. During the Movement Festival, it hosts unofficial parties for local techno enthusiasts. The entrance is hidden in the corner of a dark, dilapidated parking garage.

When asked whether he finds the title “originator of techno” a burden, Atkins smiles serenely. “I know there are a lot of expectations associated with it, but there are worse things than being called ‘originator.’ I’m happy to put up with it.” Atkins’s focus has always been on innovating and pushing back boundaries anyway; he couldn’t care less about the past. As the godfather of black electronic music, he developed the blueprint for techno with his first music project Cybotron way back in 1981, and went on to influence many young musicians who could play the current generation of synthesizers and were hungry for something new. His first synth was a Korg MS-10 that he cajoled his grandmother, who raised him, into getting. A Hammond organ player, she saw the technical device that her grandson coveted as a legitimate heir with new features. Alongside German electronic pioneers Kraftwerk, Juan Atkins’s earliest musical influences were chiefly Parliament and Funkadelic headed by mastermind George Clinton, who also made Detroit his creative incubator.

The lights of Comerica Park, where baseball fans cheer for their home team.

According to Atkins, “Detroit has always produced groundbreaking music. Maybe this has something to do with its special geographical location or the fact that the city is built on the site of Native American battlefields. One thing is for sure: Detroit was predestined for creativity.” Perhaps it’s because the city is home to one of the biggest black communities in the United States. Or it could be linked to the suffering caused by the city’s decades-long decline—the gutted houses, many industrial wastelands and the fact that people have to make their own entertainment. People don’t just bump into each other here. Nobody walks around this empty city. “Where there aren’t any people, nothing’s going on,” says Atkins drily.

In 1981 Juan Atkins founded the band Cybotron with Richard Davis alias 3070. Their first maxi-single sold 15,000 units, but the group split up after their first album. At the start of the eighties, techno was radically modern, downright futuristic, and its pioneers also foreshadowed the digital era. “If we’d had today’s digital capabilities back then, we wouldn’t have had to devote so much time to the technical side of our ideas,” says Atkins, envious of the current generation of musicians. “On the other hand, we could concentrate fully on our music because there was nothing to distract us in this dead city.”

When the melodious soul sound fell out of favor and Detroit’s acclaimed Motown label could no longer blaze a creative trail, it was time for something new. Techno is the music of new beginnings, of hope and faith in a better future. Based on four-four time, the chilly, monotonous techno beat is an apt reminder of the Motor City’s hard, pounding rhythm and its gigantic, steel automotive plants. At times rough and raw-sounding, Juan Atkins’s compositions can also be elegant and almost whimsical—providing a true musical reflection of his hometown of Detroit. “I’ve always made music intuitively. Naturally, my mood also plays a role when I’m composing. What’s more, making music was the best possible way to escape everyday life in a city where circumstances were so dire.”

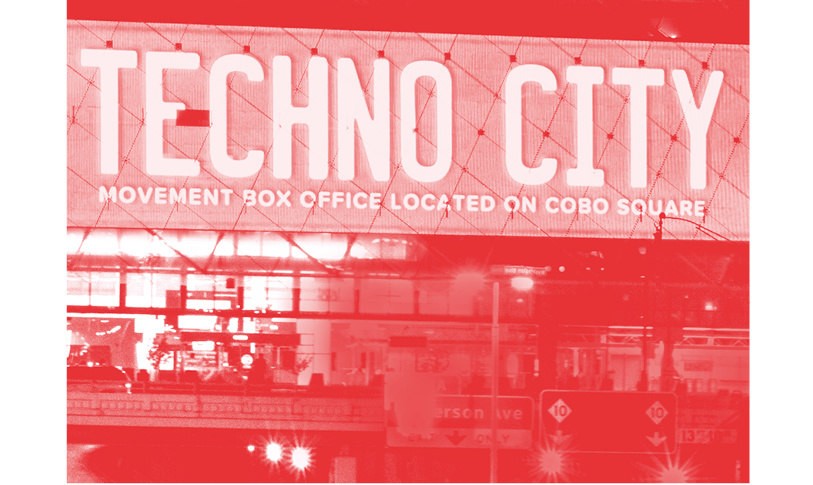

Today, Detroit officially bills itself as Techno City. The moniker references Juan Atkins’s song of the same name, which is a musical homage to his hometown.

Techno is the music of

new beginnings.

On Saturday nights, Downtown fills up with cars, their owners all eager to flaunt what they’ve got.

The open-air festival Movement Detroit attracts tens of thousands of ravers each year. DJs and bands hailing from all over the globe revel in the glory just like Detroit’s techno veterans, who remain the main attraction.

Since spring 2018, the City Council is again in charge of its own finances after Detroit was forced to declare bankruptcy in 2013.

A walkway joining Joe Louis Arena with a parking garage spans an eerily deserted lot. The stadium was home to the NHL’s icehockey team Detroit Red Wings until 2017. Today, the futuristic venue, which opened in 1979, is defunct.

Someone who owes a lot to techno and consequently to Detroit is Berlin-based cultural manager Dimitri Hegemann. The German owns the capital’s legendary club Tresor and markets the music label of the same name. Juan Atkins and Dimitri Hegemann met in the early nineties when Tresor released an album featuring Atkins as composer. The Detroit-Berlin connection has been going strong for 30 years now and it’s become a matter of course to name the two cities in one breath. Both are synonymous with a new dawn and creative energy. In addition to their passion for music and counterculture affiliations, Atkins and Hegemann are bound by a shared understanding of the positive energy that culture and especially music can unleash. The cost of living is low in an urban environment that needs regeneration.

Such places attract young people and those who want to make their mark and shake things up. “I’ll open a Tresor in Detroit the moment the last call time is dropped.” To move that agenda forward, Hegemann speaks regularly to the Detroit City Council and is in personal contact with Mayor Mike Duggan. The cultural manager does the math as follows: “Twenty percent of Berlin’s tourists come for the nightlife—that’s roughly eight million people per year and a vital economic driver. Obviously, the clubs have to stay open until morning.” It’s what is known as the nighttime economy. Thanks to the dedication of international champions like Dimitri Hegemann, the status of musicians and techno has risen tremendously in Detroit. Juan Atkins is also aware of this: “You simply can’t deny that techno and its artists have put Detroit on the map globally. This is the locus of electronic music’s evolution.” The group has already pinpointed a hotspot for nightlife and creative talent: Milwaukee Junction, north of Downtown. This is not only where the music label Underground Resistance and others in the industry have set up shop, but also where Hegemann would like to open Tresor Detroit. He’s confident it would be the world’s most successful club. Which is music to many people’s ears.

In any case, Detroit seems to finally be charting a course for the future. Working together with architects and city planners, urban designer Julio Cedano is part of the mayor’s young team tasked with shoring up those neighborhoods which have proved best able to defy decline in the past. “Neighborhoods with the fortitude to hold out against 30 years of decay are the ones that will carry the city forward again. The people there are deeply rooted and know best what’s needed for a return to glory. They will draw others into the process.” And here we come full circle. Detroiters have rediscovered their vitality. It’s a city with a contagious spirit. Julio comes from Boston. So what on earth made him opt for Detroit? “Something big is unfolding here. I want to be part of that and bring about change.” The beat goes on.

Further photo credits: Rouven Steinke, Jodelli / Wikimedia Commons, Simon Roloff