“Robots shouldn’t simulate feelings”

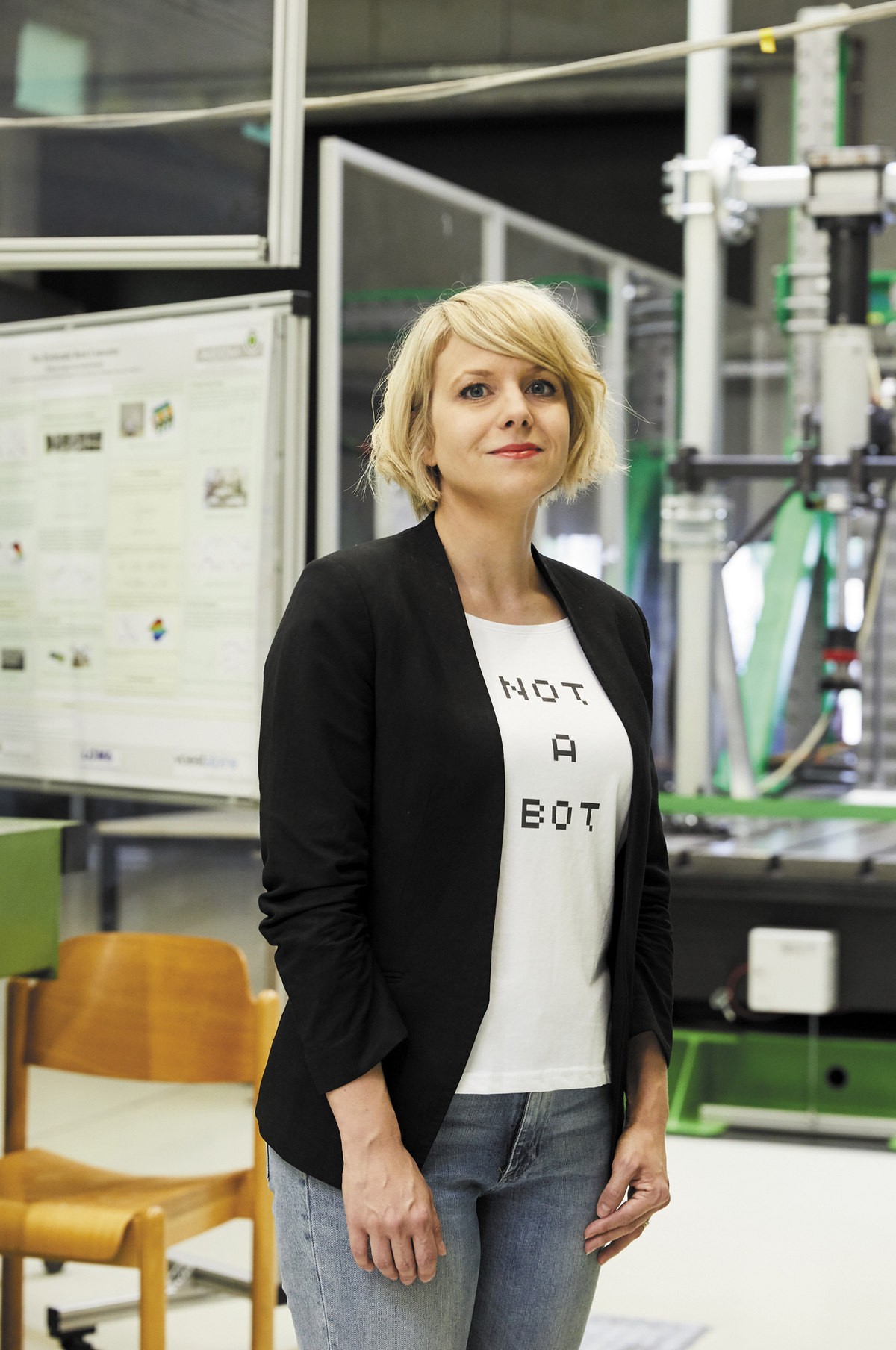

Robopsychologist Martina Mara conducts research at the Johannes Kepler University Linz on how humans and machines can live and work together in harmony.

Jan Strahl (copy) & Paul Kranzler (photo)The Audi Magazine: Martina, you are the world’s first professor of robopsychology. What career path led you to this position?

Martina: I took a master’s in communication sciences in Vienna, specializing in media psychology, and later completed a PhD in psychology at the University of Koblenz and Landau. There was already a strong focus on human–robot relations in my doctoral thesis. Alongside my studies, I also worked for many years in the non-university technology and design research sector, where I had a lot of contact with engineers, interaction designers, artists, hackers, and company representatives. As a result, for me interdisciplinarity isn’t just a trendy buzzword, but something truly everyday. It’s also meant I’m well equipped to talk even with hardcore tech nerds. That’s a big advantage! After all, I can’t research the psychological implications of AI and robotics without being in constant dialogue with the people who are developing these technologies.

What exactly does a robopsychologist do?

Well, let’s get one thing out of the way first: I don’t treat robots on a psychiatrists’ couch! In my lab, we don’t study the psychology of robots (as is occasionally a theme in science fiction), but rather the well-being of the growing number of humans who will have to interact with robots. Questions that we deal with include: what fears do people have of autonomous technologies, and where do they come from? How can robots be designed so that different interacting partners, from laypeople to expert users, feel safe and secure rather than, say, dominated? How can smart machines’ states and goals be made as transparent and intelligible as possible to people? In terms of methodology, we build on psychological theories and methods, but also attempt, on the basis of quantitative empirical results, to identify design factors for practical technological development. Where it makes sense to do so, I combine traditional social sciences methods with experimental approaches such as design thinking.

Whereabouts do we already encounter robots in everyday life? In what fields is there (currently) a particular demand for robopsychology?

Apart from Roombas and robot lawnmowers, which have already made their way into people’s living rooms and front yards, and the occasional humanoid assistant being tested in supermarkets or shopping malls, we don’t yet encounter robots very often in day-to-day life. The more powerful machines in particular tend to be kept behind the scenes. In manufacturing, for example, heavy-duty robot arms operate in cages or cordoned-off areas, and once they’re turned on people have to keep their distance. In care homes, robots are used to transport bedlinen, but so far they’ve only been used in basements or elsewhere in the background. The exciting thing is that thanks to constant improvements in sensor technology, robots are now gradually becoming safe enough to emerge from behind the scenes and interact even with people who haven’t received special training. And of course, whenever humans and autonomous machines come into contact, it’s very interesting for robopsychology: that applies not just to the new collaborative robots in production and assembly and to robots in care homes and hospitals, but also to self-driving cars, drones, and what are often described as “social” or “companion” robots.

What should developers or designers of robots bear in mind from a psychological point of view?

I believe that in most areas of application, it would be absurd to develop highly human-like robots, because we know from psychological research that they often come across as frightening or creepy. In cases where social and communicative aspects are particularly important, for instance in the care sector, then a care robot that gives a poor simulation of compassion can only be a bad idea. In one field experiment that I often cite, hospital patients were touched on the arm by a robot. Half of them were told that the robot was trying to comfort them. The other half were told that the touch served a medical function: for example, the robot was taking measurements of the surface of their skin. The second group was far more accepting of the robot’s touch than the first. However, the fact that simulated emotions in machines aren’t always well received doesn’t mean that there’s no role for robots in the care sector. Quite the contrary: I believe there’s actually great potential, from autonomous bedlinen transport to exoskeletons to assist with lifting.

Martina Mara has been professor of robopsychology at the Linz Institute of Technology (LIT), Johannes Kepler University Linz, since April 2018. She writes the column “Schöne neue Welt” (Brave New World) for the newspaper Oberösterreichische Nachrichten, in which she discusses the social impact of digitalization and new media.

How can concerns or fears about robots be alleviated, some of which may be based on sci-fi dystopias like the Terminator movies?

Yes, diffuse fears are often linked to the public perceptions and media discourse around a topic. I regard two factors as crucial on this front. The first is education. At the moment, there are so many mystical images and concepts swirling around robotics and artificial intelligence – learning systems, neural networks, weak and strong AI – constantly accompanied by these images of highly human-like robots. There’s barely ever any explanation of the current state of the technology, how it works, or the fact that very, very few developers are remotely interested in humanoids. It needs to be demystified. The second factor is positive visions of the future. There’s far too much discussion about dystopias and robotic overlords. Critical reflection on technological progress is of course important, but we also need positive images of the future that we can work toward as a society. Ideally, these images would show how intelligent machines can complement us human beings, support us as tools, perhaps even free up more time and resources for the things we consider important or enjoyable. The idea of humanoids reading bedtime stories to children doesn’t fit this picture.

Would it make sense to have campaigns like those used to help integrate minorities or marginalized groups?

I believe that users should have to learn as little as possible. Too much lecturing and explanation will only make them skeptical again. There needs to be a focus right from the start of the design process on creating robots that can be seamlessly integrated into our day-to-day lives. We don’t need a campaign for robot rights or anything like that. Instead, we should be redoubling our efforts to improve human rights.

The term “robopsychology” was first coined by the science fiction author Isaac Asimov. However, in his stories the robopsychology experts really do analyze the mental states or artificial intelligence of robots. How likely is it that there will one day be robopsychologists of that kind too, and would that also be an interesting challenge for you?

That would first require us to create robots with consciousness, or at least the capacity for emotional experience. Speculating about the implications of those sorts of sci-fi creatures and whether they would need psychological help is a fun topic over a glass of wine with friends in the evening. But it’s not something that’s relevant to my everyday profession, except that the name “robopsychologist” leads many people to mistakenly assume we’re on the verge of human-level AIs, to which they attach many diffuse anxieties. In reality, however, there isn’t a single research project that comes anywhere close to genuine artificial intelligence. That’s not even a long-term prospect. So psychological treatment will remain the exclusive preserve of humans.

The final question: what is your vision for the future co-existence of humans and machines?

A harmonious one in which they complement each other with their respective strengths.