Curiosity is what drives me

The polymath Carsten Nicolai has enjoyed equal success on the international stage with his electronic music and his art installations. Mobility is integral to the way he thinks.

Jan Strahl (interview) & Sebastian Mayer (photo)

The Audi Magazine: It occurred to us that mobility might stand apart from technology as an outlook on life or way of thinking that’s closely intertwined with creativity and innovative spirit. And you are arguably the poster child for this manifestation of mobility.

Carsten Nicolai: More than anything else, curiosity is the spark that keeps me moving. It’s what drives me. In my view, it’s incredibly important to remain inquisitive and open to new things. I’m fascinated by fundamental theories, such as quantum physics, that not only offer a completely different way of looking at the physical world but also open philosophical doors and provide material for me to engage with as an artist. Another key source of inspiration are the major utopian visions. To this day, I’m inspired by the book 'Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth', which Buckminster Fuller wrote at the end of the sixties. In it, he makes a compelling case that humanity has been given this spaceship but we first need to write the operating manual to keep it functioning properly. Back then, Fuller was already addressing topics that are even more pressing today—the environment, sustainability, responsibility. What is especially inspiring in terms of my work is the idea that everything is interconnected and interdependent. You can’t look at anything in isolation.

An idea that you were already grappling with when you studied landscape architecture in Dresden in the early nineties.

Exactly. Basically we were trained to rehabilitate large tracts of land devastated by brown coal open-pit mining. It’s actually very different from horticulture and instead involves recreating whole habitats. That’s where I learned to appreciate the value of seeing the big picture—recognizing correlations and synergies—which is so important to my present work as an artist.

Born in Chemnitz in 1965, Carsten Nicolai’s interest in the visual arts and (electronic) music began back in his school days. He describes himself as an “autodidact who had to think outside the box to find the materials I needed in East Germany, where resources were scarce.”

Nicolai’s work appears in international exhibitions such as documenta, the Venice Biennale and Art Basel Hong Kong.

Carsten Nicolai calls the book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth by visionary, designer and architect Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) “a source of inspiration.” The author imagined Earth as a fragile spaceship traveling in a hostile universe.

Today, it’s not just artists, designers and actors who are expected to be creative. It seems as if office workers and engineers also have to be far more innovative to meet the challenges of digitalization and globalization. Are we suffering from a creativity deficit?

I think everyone is born with the potential to be creative, but that ability has to be nurtured from a young age. As a lecturer at the art academy in Dresden, I see fostering creativity as one of my main responsibilities—but above all viewing creativity as an asset. In our society, which puts a price on everything, creativity itself still isn’t considered a resource. This way of looking at it will ultimately diminish our country’s innovative capability. Ignoring this development too long means eventually forfeiting economic dominance.

So, creative thinking should pervade all levels of the hierarchy and all positions in the corporate world and in society as a whole?

Of course, there must be demand for creativity, and it has to be channeled. Berlin is a good example of this. Here we have a livable city for young, creative people that has become a magnet for attracting innovative movers and shakers. And I’m not just talking about the visual arts or music but also technology, Internet culture, lifestyles and start-ups in many different fields. This has led to a curious situation in which we now have a surplus of creative minds that society is still struggling to absorb. In other words, there is great potential, but the structures in place currently lack the mechanisms for leveraging it.

Silicon Valley also has enormous creative potential. It seems there it’s being efficiently channeled to where it’s needed. After all, this is the environment that has produced the most successful companies in the world today.

I’m very skeptical about that. “Silicon Valley” has this kind of magical ring to it, but ultimately it boils down to an intensely business-oriented approach that aims for direct value added. All innovations there are clearly geared toward commercialization, not long-term success. That’s pretty problematic in my view. It means that any innovation that can’t be instantly monetized falls by the wayside, and that could come back to bite us. Germany appears to be much better positioned in this regard. Thanks to the way industry developed here over time and maybe our political structures, Germany has never been extremely centralized. Large industrial companies are scattered throughout the entire country, including in small villages and rural areas. I think that’s a huge advantage. For one, the sheer number of patents held in Germany points to enormous innovative strength. These structures seem to me to be more efficient and sustainable than a closed ecosystem like Silicon Valley with its resident mega-corporations.

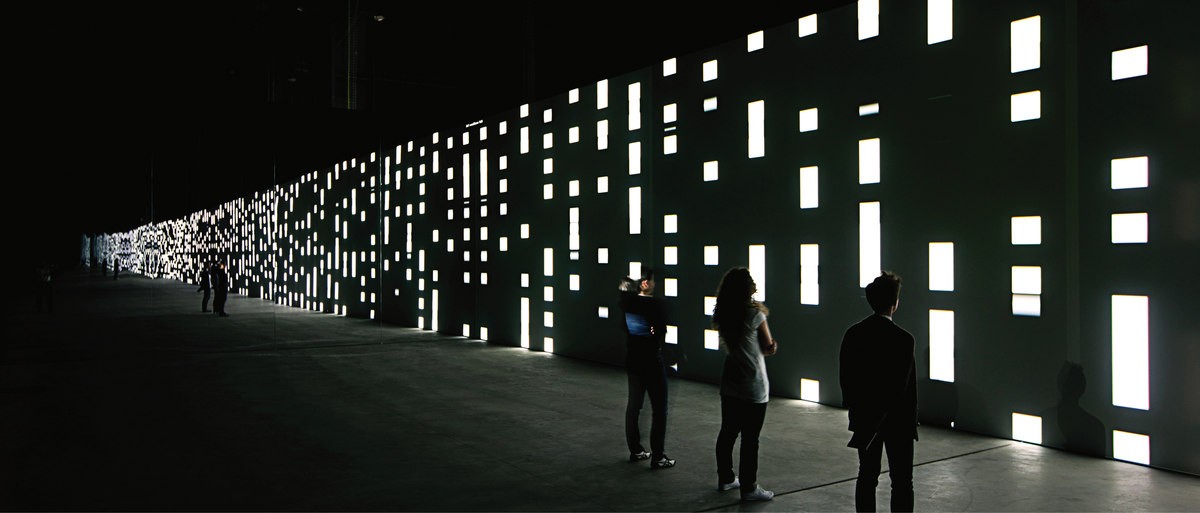

unidisplay, 2012 (with viewers in foreground): real-time projection, large-format screen, mirror, dimensions variable | Artwork: Courtesy Galerie EIGEN ART Leipzig/Berlin and Pace Gallery, Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan © vG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Agostino Osio

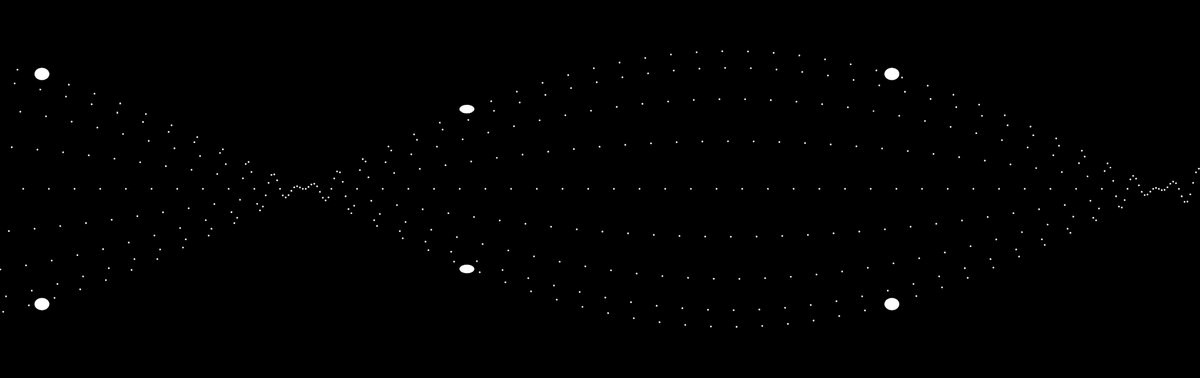

unicolor, 2014: real-time projection, large-format screen, mirrored walls, bank of speakers, dimensions variable | Artwork: Courtesy Galerie EIGEN ART Leipzig/Berlin and Pace Gallery © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Julija Stankeviciene

unitape, 2015: Real-time projection, mirrored walls, bank of speakers, dimensions variable | ARTWORK: Courtesy Galerie EIGEN ART Leipzig/Berlin and Pace Gallery © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, PHOTO: Uwe Walter

In Silicon Valley, failing now and then is good form. An entrepreneur must have run at least one startup into the ground in order to be taken seriously. At least in this regard your approach as an artist is similar?

I seize moments of crisis in order to channel them into my creative work, so I would recommend that any company not only plan for failure and mistakes but intentionally elicit them. It’s like discarding a rough draft in any creative pursuit. Especially after a major project, artists (like anyone else) fall into a sort of abyss; suddenly you are unable to move forward. At first, you try not to founder, but this crisis is precisely what enables you to reinvent, to reset and then revisit fundamental assumptions. Major corporations often have structures set up to prevent this type of “failure.” There is no option to discard a rough draft, so it’s impossible to get a fresh start once the ball is rolling on a project. We should not fear crises.

Do you think there’s such a thing as a bad result or mistake in music or art?

Personally, I’m not interested in finding solutions or producing results but rather in developing principles that generate endless variations of possible results. In my sound visualization projects, I use software- or hardware-based principles that continually create new and unexpected images out of the resulting data, frequencies, phase shifts and dynamics. The sound itself becomes a creative force and is the catalyst for an image. I can then present this “frozen moment” as a work of art, but the process that birthed it is more important to me.

Software that can create art out of sound? That brings us to a topic critical to mobility in the future—artificial intelligence. What intrigues you about AI?

The greatest talent we as humans possess is the ability to make mistakes and learn from them. Computers aren’t allowed to do that: The possibility of making a mistake has been eliminated. We expect no less than perfection from our machines. Only when computers get the chance to make mistakes, to lie or use other mechanisms particular to humans, only then can we really start talking about artificial intelligence. The result is something many of us fear greatly: the creation of a computer system better than we are. But the question here is, what do we really want? A perfect computer or artificial intelligence? We’re all familiar with science fiction movies such as 2001: 'A Space Odyssey' or 'Terminator' that feature situations in which machines are superior to humans and ultimately attempt to enslave us.

Keeping this scenario in mind, would you like to be chauffeured around by a self-driving car?

Definitely! Those are systems we will likely be using in the near future. In fact, they’re similar to the ones we have long trusted in airplanes. If the technology works, I’d be very happy to see self-driving cars on the road in a few years’ time. I already gladly use modes of transportation in which I don’t have to take the wheel myself, because then I can devote myself to more inspirational pursuits. Cars that do the driving give me more freedom. Self-driving cars are not an example of artificial intelligence, though. They move within parameters programmed and dictated by humans.

Nicolai composed the soundtrack to the Hollywood block-buster 'The Revenant' and several other albums with Japan’s Ryuichi Sakamoto under the pseudonym Alva Noto.

unidisplay, 2012: real-time projection, large-format screen, mirror, dimensions variable | Artwork: Courtesy Galerie EIGEN ART Leipzig/Berlin and Pace Gallery © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Studio Carsten Nicolai

In 2013, Nicolai partnered with Olaf Bender to form Diamond Version and toured Eastern Europe as Depeche Mode’s opening band.

Do you like to listen to music in the car?

Yes, of course. In fact, cars are one of the best places of all to listen to music. They have great acoustics: the interior provides an ideal listening environment similar to a recording studio. When I compose a new piece of music, I first test the final mix in my car. If the track works there, then it’s cool.

Which of your compositions would you recommend for an extended car trip?

I think all of the albums I recorded with Ryuichi Sakamoto are really great driving music, particularly the soundtrack to the film 'The Revenant' and my 'Xerrox' series. When I need more momentum and motivation, I like to listen to my Univrs album.

Would it be the simplest solution for an international artist like yourself to be able to “beam” directly from point A to point B? From Berlin to Hong Kong in a fraction of a second?

Using a transporter like on the starship Enterprise is a childhood dream of mine, and sometimes I definitely wish this technology were available. However, I also think it’s a good thing when traveling to experience how vast our world is, how diverse it is, and I actively search out the special character or identity of the places I visit. Luckily, thanks to digitalization, I always have small, portable tools with me that I can use for work. You could say I carry my studio with me. That lets me make the most of the eleven-hour flight to Japan. Some of the best inspiration comes to me on the road.

We’ve now asked you several questions regarding various aspects of mobility. Which issue do you consider most critical?

I wonder if we couldn’t ultimately find a socially acceptable solution for personal transportation in cities. At the moment, it doesn’t seem likely, but then a little bit of individual freedom will be lost. That’s why I ask myself whether there aren’t innovations on the horizon allowing for both sustainability and individuality. Maybe electric motors are a solution, or it could be something completely different.

Further photo credits: René Habermacher, Simone Cecchetti /Getty Images, Artwork: Courtesy Galerie EIGEN ART Leipzig/Berlin and Pace Gallery © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Art Basel; Dirk Haun