Sustainable city

Denmark’s capital is not only considered one of the most livable cities, but also aims to become the world’s first carbon-neutral metropolis by 2025.

Daniela Schröder (copy) & Benne Ochs (photo), Raymond Biesinger (illustration)

Twenty minutes, that’s the benchmark. When searching for a new apartment or for the best childcare facility. When deciding whether to accept a job offer. When choosing the most laid-back bar for an after-work drink or the perfect restaurant for a weekend brunch. “20 minutes,” says Mikael Colville-Andersen, dismounting from a white racing bicycle. “In Copenhagen, everything takes just 20 minutes by bike.” He laughs. “At least, that’s how it feels.” Pushing his sunglasses back into his hair, Colville-Andersen slides the bike into a mass of two-wheelers parked outside a container-like building. Trangravsvej 8 on Papirøen, a mini-peninsula within Copenhagen’s old port, is his office address. Dressed in a dark-gray shirt, jeans and white sneakers, Colville-Andersen previously worked as a movie director. These days, he rarely has time to shoot movies. For several years now, Colville-Andersen has been Denmark’s leading cycling lobbyist, and nobody personifies the bicycle movement quite like he does. His consultancy firm has designed cycle-path systems for almost a hundred cities worldwide, including Dublin and Detroit. “But Copenhagen takes cycling more seriously than any other city,” he says. “Over the past two decades, an infrastructure has been created here that has made the bicycle an attractive and competitive mode of transport.”

The Danish capital refers to itself with pride as the “City of Cyclists.” Virtually no other city pushes the bike harder as a means of mobility; green mobility plays a major role in Copenhagen’s future plans. Always highly ranked in the lists of the world’s most livable cities, Copenhagen also wants to lead the way in environmental terms. To this end, the city aims to become the world’s first carbon-neutral metropolis by 2025. This does not mean that the inhabitants will then no longer generate any climate-damaging carbon dioxide at all. In addition to avoiding CO2 emissions, this goal involves offsetting greenhouse gas emissions at one location with environmentally-friendly measures at another. In so doing, Copenhagen is taking a 360-degree approach: From traffic and building to energy and water—the entire urban development is focused on the goal of being “green and clean.” CO2 emissions in Copenhagen have fallen by 38 percent since 2005, and the city aims to eliminate a further 900,000 tons of carbon dioxide by 2025. An ambitious goal. However, the vast majority of Copenhagen’s residents are behind the plan, with 87 percent happy for their city to become carbon neutral. Quite apart from that, it’s not just about improving the quality of life in the city, argues Morten Kabell, Copenhagen’s Mayor of Technical and Environmental Affairs: “In the fight against climate change, major cities across the globe play a key role because it is they that cause most of the world’s CO2 emissions.” So, he argues, Copenhagen is partly responsible for the world’s climate. In conclusion, Kabell says: “With our climate initiatives, we want to play a leading role in the international arena and inspire other cities to do something similar.”

A stone’s throw from cycle-path-planner Colville-Andersen’s office, a very unique bridge spans the old harbor basin. Opened in 2006, the Bryggebroen became the first new bridge between the harbor side and the old city in seventy years. The design is functional, simple and modern—typically Danish in style. Specially built for cyclists and pedestrians, it was the construction project that kick-started the cycling movement in Copenhagen. Today, Bryggebroen is one of numerous bicycle bridges in the city, with others under construction or projected. A total of 1,000 kilometers of cycle paths wind their way through the greater Copenhagen area with its population of two million—that’s on top of the hundreds of kilometers of bicycle lanes on the roads. Cycling in Copenhagen is convenient and safe.

“Copenhagen’s track record of pilot projects is unique. The city experiments with good ideas to see if they become amazing ones.”

Each day, more than 8,000 cyclists use the connection via the Cykelslangen, the famous bridge with its orange two-way bike lane that snakes across Copenhagen’s inner harbor basin.

The European Environment Agency has its headquarters in Copenhagen. Since 1994, it has been responsible for providing policymakers with information and data about the status of and changes in the environment in the EU.

Lying just 3.5 kilometers off the coast of Copenhagen, Middelgrunden is the world’s first commercial offshore wind farm. Ten of the 20 wind turbines are owned by 8,600 private shareholders.

Even visitors to the city quickly find their way around on two wheels. The routes are separated from cars and pedestrians, indicated with symbols and markings and wide enough to permit stress-free overtaking, even with Denmark’s export hit, the cargo bikes. Traffic lights along the main routes to the city center are phased to provide a “green wave” for cyclists traveling at a constant speed of 20 kilometers per hour; LED lamps in the asphalt act as a speed control. Despite these measures, cyclists now often experience tailbacks. 61 percent of downtown residents and 41 percent of Copenhagen’s suburban population travel by bicycle every day. Between them, they cover a daily average of 1.4 million kilometers. Local politicians see cycling as a key element of the city’s identity, and central Copenhagen is set to become car-free by 2025. To make it happen, the administration wants to expand the bicycle infrastructure. The biggest project involves 28 bicycle highways with separate speed lanes that will connect the suburbs to the city center. To combat congestion, the city draws on digital technology. The next generation of traffic lights will incorporate sensors that automatically switch to green whenever a group of cyclists approaches.

Copenhagen is popular, with the number of inhabitants growing. Forecasts point to an increase of 14 percent by 2025. More people, which means more traffic. More bicycles. But also more cars. By 2025, the authorities expect the number of cyclists to increase by 27 percent and the number of cars by 20 percent, mainly in the suburbs. To meet the climate targets it has set itself, Copenhagen is expanding the infrastructure for alternative drive systems: charging stations for electric cars, hydrogen fuel stations, reduced parking charges for vehicles equipped with new drive systems. The authorities themselves are setting a good example: 64 percent of the administration’s fleet of vehicles already run on hydrogen or electricity, and new public buses are required to have an electric motor instead of a diesel engine.

It’s shortly before nine in the morning at the University of Copenhagen’s medical faculty. Researchers and students stream into the 15-story building. Opened in January 2017, the Maersk Tower is regarded as the most cutting-edge educational campus building in Denmark. It is packed with energy-saving technology and clad in copper-covered shutters, which follow the path of the sun and provide shade—an air conditioning system that does without electricity. The copper also gives the building an unusual appearance, “the influence of the weather causes the color to change over time,” says Thue Borgen Hasløv of Copenhagen-based architectural practice C. F. Møller, which designed the Maersk Tower. The Danes are renowned for simple, attractive design that is also functional. In this case, functional means that the building is green. “Wherever a new residential or commercial building is developed, the focus is on energy efficiency and sustainability,” adds Hasløv. “Green buildings have been an important priority in the city for years, and the political move toward carbon neutrality now trains the spotlight firmly on the construction sector.” Here too, Copenhagen’s administration is setting a good example: By 2025, the energy consumption of public buildings such as schools is set to drop by 40 percent. Buildings to be renovated will be equipped with energy-saving lighting, new windows as well as the latest insulation technology. While this reduces CO2 emissions from the building sector by a mere seven percent, energy conservation is still the most effective way to curb emissions.

The Audi A3 Sportback e-tron with plug-in hybrid drive is a practical everyday vehicle for cities like Copenhagen. It offers up to 50 kilometers of electric driving in city traffic with an extensive range and excellent handling over long distances thanks to the powerful four-cylinder internal combustion engine.

At the same time, energy generation is part of the plan: The city aims to install more than 60,000 square meters of solar modules on public buildings over the coming years. This is equivalent to roughly eight football fields. The Copenhagen International School building already demonstrates that it pays to invest in solar energy. It sits directly adjacent to a harbor basin, surrounded by old warehouses, where seagulls screech and cranes heave steel crates onto container ships. The school’s exterior shell comprises 12,000 solar panels that provide for 60 percent of its energy needs. At this school with its very own power plant, the modules shimmer a turquoise to deep blue color depending on the incidence of light and viewing angle. Numerous types of greenery grow on the roof—yet another component of the CO2 strategy. Having adopted a mandatory green roof policy on all new buildings, Copenhagen already boasts 20,000 square meters of planted roof surface, with an additional 5,000 square meters projected annually. In all the city’s climate projects, the administrative, scientific and business fields pull together as one from the out-set. The Technical University of Denmark and Copenhagen’s communal energy providers develop innovative technologies for green buildings; when researching future energy-saving methods, the authorities cooperate with the city’s leading building and real estate firms, as well as with national and international telecommunications providers.

An example of this is in Albertslund, a suburb west of Copenhagen. Here, an old industrial zone has been transformed into an open-air, high-tech showcase where two dozen companies are testing nearly 50 new street illumination systems. All lamps are converted to energy-saving LEDs and integrated sensors control the lights, which only shine brightly if a vehicle approaches. At the same time, the sensors act as data collectors: The smart lighting system is set to become a real-time information source for cyclists and drivers—ultimately relieving the situation on the roads. The technology is also set to optimize winter road maintenance and enable on-demand collection of waste. Copenhagen is already turning to LEDs, with a total of 20,000 street lamps converted and an energy saving effect of 57 percent achieved.

The capital city was also ahead of the curve when it came to considering the future and the environment in relation to energy production. How this began can best be seen from Amager Beach Park, Copenhagen’s nearby city beach and recreational area, which is roughly 20 minutes by bicycle from the town hall square. The artificial island is popular with runners and skaters, while swimmers, surfers and kayakers take to the water and families picnic in the dunes. Amager is situated on the Øresund, the narrow strait between Denmark and Sweden, and is not far from the imposing Øresundsbroen cable-stayed bridge almost eight kilometers in length that links the two countries. A stone’s throw from Amager, there is another colossal structure in the water, which is a source of pride not only to the residents of Copenhagen, but to all Danes: Middelgrunden. Comprising 20 offshore wind turbines that spin off the coast, the world’s first commercial offshore wind farm is just three and a half kilometers from the beach.

Since the 1990s, all aspects of urban development in Copenhagen have followed a consistent sustainable policy: from traffic planning all the way to alternative energy generation.

The future of on-street parking: Street lamps that also function as charging poles (such as those by Ubitricity) would provide comprehensive charging networks for electric vehicles in cities. The technology is at an early stage of production maturity.

The Copenhagen Climate Plan has earmarked the equivalent of around 175 million euros for mobility projects. They are set to curtail the city’s CO₂ emissions by eight percent.

Thanks to the Mode 3 cable, the Audi A3 Sportback e-tron can be fully charged at public charging points in around 2.5 hours.

Copenhagen is converting all of its street lights to energy-saving LEDs. They are equipped with sensors so that the lights only shine brightly if a vehicle approaches.

With our climate initiatives, we want to inspire other cities.

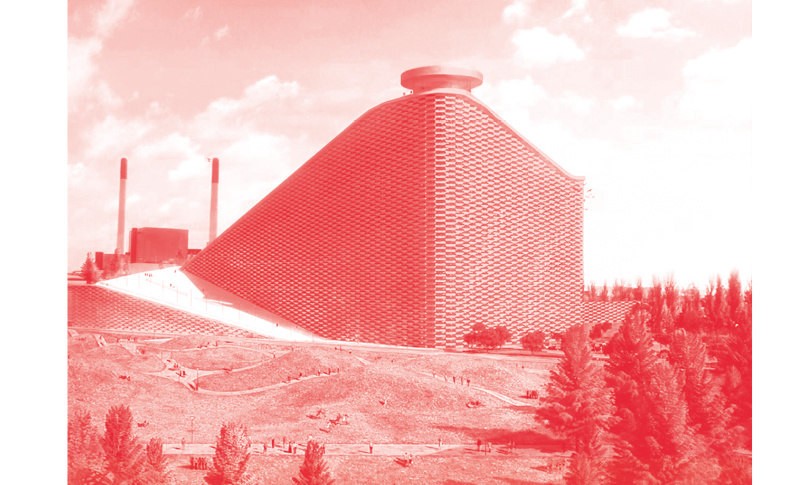

Winter sport by the sea: Just five kilometers from downtown Copenhagen, a 440-meter-long ski slope is being constructed on the roof of the Amager waste incineration plant planned by architect Bjarke Ingels. It is scheduled for completion in 2018.

When oil prices skyrocketed during the 1970s and industrialized nations were looking for alternative sources of energy, the Danish government decided against nuclear power and invested instead in renewable energy sources such as wind power. Even then, the Danes already had a strong environmental awareness. “During the mid-nineties, a group of Copenhagen engineers hit on the completely crazy idea of refining wind turbines so that they could be installed in water,” explains Middelgrunden manager Erik Christiansen. “Actually, it wasn’t such a crazy idea after all because a capital city simply doesn’t have the space to devote to generating green energy. But we do have the sea on our doorstep—so we use that instead. Middelgrunden became not only a national symbol of the shift toward green technology, but also the model for partnerships between energy providers and citizens,” says Christiansen. The offshore wind farm is organized as a communal cooperative, a traditional Danish economic model that is to this day still diversified through all sectors. Ten wind turbines are owned by Danish energy company Dong, while ten others belong to Middelgrunden’s 8,600 private investors and shareholders. The wind farm supplies a good four percent of the electricity consumed in Copenhagen, and that figure is set to rise.

Production of electricity and heat still generates most of Copenhagen’s CO2 emissions—which in turn means that this field offers the greatest potential savings. The city has set its sights on achieving 80 percent of the total target by expanding new forms of energy: wind power and solar energy, but mainly by replacing coal power with renewable biomass. Two power stations will run solely on wood pellets in the future. A new waste incineration plant that uses the “waste to energy” principle is already supplying heat and power to thousands of Copenhagen households. The plant’s futuristic architecture conjures up images of luxury Arabian hotels. And like any practical solution in Copenhagen, it not only looks good, but is also built for fun: The architects constructed a ski slope on the slanting roof of the designer power station.

Copenhagen has spent the equivalent of almost 1.7 billion euros reconfiguring its energy sector, while the overall climate plan investment totals some 27 billion euros. It is an investment that will pay off, argues Copenhagen’s Mayor of Technical and Environmental Affairs. Exports of green technologies alone are increasing year on year by around twelve percent, according to Kabell. Most importantly, however, this is creating jobs. In the construction, energy and transport sectors, implementation of the climate plan is expected to create over 30,000 new full-time positions. Kabell’s bottom line: “Things that make sense for environmental reasons also boost the economy.”

What’s good for the environment is also good for the economy.

The example of Middelgrunden shows that the strategy is paying off: The pioneering wind farm made Denmark the global leader in offshore renewable energy. In terms of both consumption and technology, the newly developed turbines became the archetype for all offshore turbines with which Danish manufacturers carved a reputation for themselves worldwide. Companies in Copenhagen became specialists in operating and maintaining the nearby wind farm. The same firms are currently planning Middelgrunden’s regeneration. Virtually two decades after the project began, the cooperative is removing the old wind turbines and installing new ones. “Investments in green energy are not just good for a city’s environment and quality of life,” says Middelgrunden manager Christiansen. “They also benefit the economy and competitiveness.”

And life is good in a city that espouses ecological ideals. Clean air and plenty of green spaces are a key health factor. When combined with attractively designed public spaces, they also enhance a city’s appeal. Ørestad—Copenhagen’s newest district situated on Amager Island—shows how it’s done. The planning process began 25 years ago, with the goal of developing an urban district pointing the way to the future. Ørestad is dominated by buildings constructed of wood and glass along with residential homes featuring small gardens, extensive parkland and trees. “I’m living in a big city, but it feels like the countryside,” says Nina Truelsen, who moved with her family from the city center to Ørestad three years ago. The district is not directly by the sea, but water is omnipresent here. Ten kilometers of artificial canals run through Ørestad. “The water is cold and clear all year round,” says Truelsen. The good water quality is ensured by the local administration with the help of specially developed technology that filters soiled rain water from streets and roofs before it flows into the canals. Clean water right outside the door—on the path to a completely green city, Copenhagen also looks after the little details. Or as Mayor Kabell puts it: “You must also have the courage to embrace unconventional solutions that give the city a profile and individual districts a hallmark and identity all of their own.” It will not be easy to achieve the important goal of carbon neutrality, he says. “There are many hurdles and challenges to overcome,” Kabell concedes. “But we will succeed.” Anyway, the CO2 issue is just a first step. The next target for Copenhagen is to abandon coal, oil and gas entirely by 2050.

Danish sense of style: When Copenhagen residents rejected the initial design for the Middelgrunden wind farm using three straight lines, the planners placed wind turbines in the water in the shape of a giant curve.

Completed in 2017, the Copenhagen International School with 1,200 pupils is not only the biggest school in the city. Its more than 12,000 solar modules also make it one of the buildings with the largest expanse of solar panels in Denmark.

Copenhagen’s citizens want even more wind power; 85 percent support initial proposals for additional wind turbines along their coast.

Audi A3 Sportback e-tron fuel consumption combined (in l/100 km): 1.8–1.6. Power consumption combined (in kWh/100 km): 12.0–11.4. CO₂ emissions combined (in g/km): 40–36. Where stated in ranges, fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions as well as efficiency classes and power consumption depend on tires/wheels used.

Further information on official fuel consumption figures and the official specific CO₂ emissions of new passenger cars can be found in the guide “Information on the fuel consumption, CO₂ emissions and electricity consumption of new cars”, which is available free of charge at all sales dealerships and from DAT Deutsche Automobil Treuhand GmbH, Hellmuth-Hirth-Strasse 1, 73760 Ostfildern-Scharnhausen, Germany (www.dat.de).

Further photo credits: Wikimedia Commons, Ubitricity, Bjarke Ingels Group