Assessing society’s needs and people’s desires

Audacious private homes, diverse cultural buildings, but above all innovative and high-quality projects for the socially disadvantaged—in Los Angeles, architect Michael Maltzan is building oases for our future way of life.

Niklas Maak (copy) & Iwan Baan (photo)

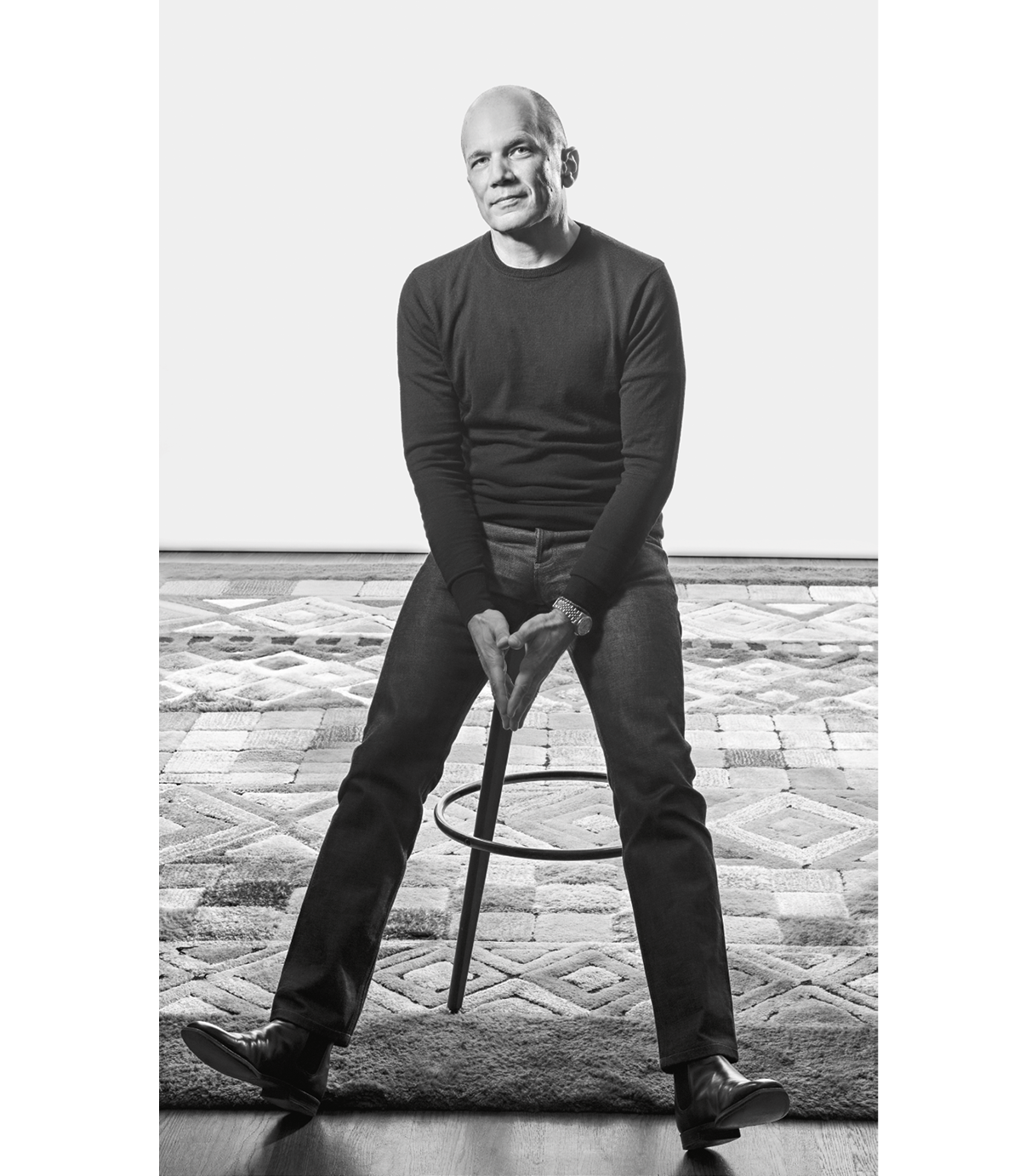

Michael Maltzan

“My vision is to create purposeful linkages between people and buildings that are aesthetically and emotionally pleasing as they are good for modern urban life.”

Los Angeles is regarded as the cradle of modern architecture. Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler, Pierre Koenig or John Lauter influenced an entire generation of architects with their designs.

At the edge of a forest north of Los Angeles offering a wide-open view over the glittering city, a most astonishing villa perches on a cliff like a spaceship that has just landed and opened its roof to make contact with the world. An old crumbling paved road leads up to what looks like a white octagon. Outwardly, it seems almost forbidding and completely impenetrable—but inside, everything is glass and openness; wrapped around an inner courtyard, the house opens onto a wide balcony. The manner in which Michael Maltzan reconciles the two fundamental qualities of a house in this villa he built in 2009 for artists Lari Pittman and Roy Dowell is unique: the protection it needs to offer on the one hand, and the openness to the world and the feeling of not being hemmed in on the other. You could walk around this house naked without being seen—while enjoying a view of the countless thousands of glittering lights and windows of Los Angeles that stretch to the horizon. However, this project alone would not have made Michael Maltzan the exceptional, multi-award-winning contemporary figure that he is. The houses for which the architect (born on Long Island, east of New York, in 1959) receives more awards and prizes than anyone else often look like elegant villas, his extravagant cultural centers like sculptures—but that is not what they are. Nor are they situated in exclusive residential areas or on glamorous boulevards. They jut out between multi-level car parks, warehouses and highways. Like shining white castles, they stand beside arterial roads and freeways, in the no man’s land of major cities. They are homes for children from disadvantaged neighborhoods and buildings for the homeless. Michael Maltzan’s status as the most important American architect of our age can also be attributed to his leading role as a champion of social change in architecture—his belief that architecture is there for everyone, not just the elite in society who have the time and money to appreciate beautifully designed airports, elegant private villas or extravagant museum buildings.

Maltzan studied in Harvard before traveling from the east coast of America to California in 1988 to work with Frank Gehry. Many young architects at Gehry’s practice dreamed of emulating their mentor’s fame by designing cultural centers, museums or concert halls. Maltzan himself might also have taken this path had fate not intervened to send him his first clients. They entrusted him with what first seemed a rather unglamorous construction job—the design for Inner-City Arts, an extracurricular support facility where each year ten thousand youths from less fortunate or socially disadvantaged families spend time after school creating works in painting, animation, ceramics and theater. What Maltzan delivered in 2008 instantly put him on the map: a little oasis of white buildings in the heart of the city, a kind of village made up of many houses and small spaces, in which nothing hints at the hardship beyond. He did not build a fortress, but a place that welcomes everyone—almost like a Mediterranean hamlet with a small theater, workshops and film studios. Maltzan won numerous prizes for his architecture of inclusion whose aim was to encourage children to come and participate. The specialist press and the public alike were awestruck: Here was someone who had successfully created a warm, inviting atmosphere using the simplest of means. Here was someone who had built a complex that might have been a luxury hotel or a stunning private residence—but instead was a home for the country’s have-nots, for the vulnerable and the forgotten. The building featured in an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2009, with architecture historian Nicolai Ouroussoff writing in The New York Times that Maltzan was the only American architect with a convincing track record of providing shelter for the poor. With just one building, Maltzan initiated a volte-face in contemporary architecture. His generally gleaming white, minimalist houses recall not only the forms of the Bauhaus movement, but also its socialist ambitions—the notion that architecture can improve and simplify life for all people, not just for the wealthy elite, that it can make it easier and more pleasurable.

The New Carver Apartments for the formerly homeless as well as elderly and disabled residents represent a new optimism in public housing for the highly vulnerable, dramatically underserved residents of downtown Los Angeles.

He followed this up with designs for the Skid Row Housing Trust, which builds accommodation in downtown Los Angeles for the homeless as well as for people who lost their homes after the financial crisis of 2008 and ended up living on the street with their children. Maltzan built the Carver Apartments, a huge circular building situated directly adjacent to freeway 10 that looks from the outside like a giant hedgehog lying on its side. At the heart of the building is an inner courtyard. A communal roof terrace of the type normally only found in luxury hotels provides a view of the city—and shows how the homeless can be provided with sanctuary and, quite literally, given a sense of perspective and a means of connecting with other people in the city. A similar role is performed by Maltzan’s Rainbow Apartments, whose 87 residential units are grouped around a large staircase and a yard on the first floor, where the homeless can gather and socialize away from the gaze of people on the street. Here too, a grand gesture allows those who have suffered mis-fortune to regain their dignity and self-belief: The beauty of the building, the aesthetic experience, the renowned “game, correct and magnificent, of forms assembled in the light,” as Le Corbusier defined good architecture, is used here to restore a sense of self-worth to people. Maltzan also designed the Crest Apartments for veterans who had lost their homes; however, his most spectacular building to date is the Star Apartment complex of 102 residences, a communal kitchen, a basketball court, gym, a bookshop and community gardens. The complex comprising prefabricated elements lifted into position on top of an existing single-floor building includes a communal area on the ground floor where formerly homeless people can meet potential employers, spend time and access the Internet. This is another aspect that tends to be forgotten: People who lose their home and their credit card can no longer readily access the Internet and are cut off from job searches and communication.

Maltzan’s philosophy of “architecture for all,” his social engagement and his belief that architecture can improve the lives of all people irrespective of wealth may also be typically American. After all, most Americans have ancestors who once fled to the New World to escape the ravages of famine and persecution—perhaps most poignantly expressed in the poem by Emma Lazarus at the Statue of Liberty in New York: “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free / the wretched refuse of your teeming shore.” It is an American tradition to believe in these tired, poor, encumbered, rejected people; to believe in society’s marginalized and forgotten. However, it is not just the fact that Maltzan’s houses restore dignity and opportunities to the poorest in society that makes them so important. In particular the apartment dwellings he builds for the middle classes are designs for the end of a consumer world that has existed since the 1950s. It was a world where every family purchased a bungalow, countless electronic devices and at least two cars in order to travel to work from the suburbs, and where the number of consumers grew solely due to the need to acquire all of these things individually. Since then, the lion’s share of all wages has been spent on rent or property loans, cars and interior fittings. Is there any other way? Could we lead a more relaxed existence by sharing things and spaces intelligently? By living in the heart of the city instead of spending hours every morning commuting to work from the outskirts?

Form follows function: During the early years of the 20th century, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius pursued the ideal of defining aesthetics solely based on function. Expensive, ornate and poorly equipped apartments were anathema to him.

There are allegedly more than 43,000 homeless people living on the street in the Los Angeles area. In the U.S., only New York has more people with no fixed abode. According to one statistic, there are 52,000 homeless people in Germany.

Mixed use for a new model of living: Maltzan grouped the 102 Star Apartments around three communal areas that are built on top of one another, a public health center at street level, the community meeting point above it, with balcony levels at the very top overlooking the city.

The Inner-City Arts Campus is a beacon project. Each year, over 10,000 at-risk youths find ways to express themselves creatively in this contemporary open-air village.

Maltzan’s structural responses, his residential complexes, represent a fundamental shift in spatial thinking. It is architects like Ryue Nishizawa, Yoshiharu Tsukamoto or Sou Fujimoto in Japan and above all Maltzan and his colleagues in America who are re-imagining our concept of urban spaces almost by themselves. Rather than dividing a city into streets, squares and apartments, they build houses like miniature cities in which eight children from four residential units can play together in a protective yard setting. They design micro-villages in which pensioners, other children or the single graphic designer can act as a surrogate family to the child whose father works in another city from Monday to Friday, to the widower, to the visitor. These new living environments are built around a new culture of hospitality with restaurant-like collective kitchens and loggia-style semi-open spaces shared by multiple residences, where people can hold communal barbecues during the summer. These innovative clusters let people check in with children or parents during work breaks, or meet friends on park-like rooftop landscapes. The buildings adapt to changing living needs and the separation of working and living has been removed as far as possible—a room can become an office, an apartment for a friend, or even a workshop.

However, the boxes can also accommodate unconventional “post-familial groups”—which will become increasingly important given that the proportion of families in the population of many cities is now below thirty percent. And the fact that a pensioner or a single father might not want to live in a single apartment but would prefer to live in other structures is something many architects fail to consider. For instance, there are no designs for eight octogenarians who want to live together in a type of shared accommodation arrangement rather than in a retirement home, just as there are no designs for three single parents who want to bring up their children together. How could housing be built so that it can once again cater for families large and small, singletons in unions that resemble extended families, a grandmother and a divorced mother with a child? All these people are by no means special cases, but members of a new demographic majority. For centuries, these types of “extended families” were the norm: A craftsman’s house or a farm was home to a close-knit core family that also included servants and maids, apprentices and various guests. In this respect, the futuristic small white villages that Maltzan is building as little oases in the no-man’s land of Los Angeles or stacking as friendly, welcoming castles are similarly a reminder of an ancient way of life that might also represent our future.

Further photo credits: Ron Eshel, Ann Rosener / Getty Images, Frank Ramspott / Getty Images