The future of mobility

Electric, connected, autonomous, shared—Bram Schot, Member of the Board of Management of AUDI AG for Sales and Marketing*, talks with mobility researcher Carlo van de Weijer about the future of mobility.

Bernd Zerelles (copy) & Robert Fischer (photo), Raymond Biesinger (illustration)

The Audi Magazine: According to a United Nations forecast, two thirds of the planet’s total population will live in cities in 30 years’ time. That means the threat of ever worsening space constraints, pollution and overtaxed infrastructure. Do urban mobility concepts need to be completely overhauled?

Van de Weijer: Mobility as an abstract concept will always exist. Since time immemorial, people have had a tendency to be on the move for about an hour a day, and that will remain constant. The only thing that has changed over the millennia is the fact that mankind has evolved and technology has taken us further. So while we now get around faster, we don’t spend any more or less time on the go. I believe we will have safe, clean ways to get around in the future. The only major problem with traffic that requires a solution is the space it takes up.

Many studies say that car traffic in urban areas occupies up to ten percent of the available space.

Van de Weijer: If by “traffic” you mean all mobility systems including streets, tracks, parking spaces, etc., it’s actually 40 percent of a city’s total area. In other words, cities are extremely badly organized. People don’t go to the city to look at mobility. They go to the city to meet other people, to experience things, to shop and eat. So something took a fundamentally wrong turn somewhere. That has to change in the future. We will see fewer cars in downtown areas because cars are not an efficient use of space. Most things that fall into the category of mobility will still be provided adequately through cars. But in terms of square footage, the way we use them is inefficient.

Mr. Schot, how does a carmaker like Audi respond to this accusation?

Schot: Cars will always be part of our mobility. But at the same time, traffic jams and parking scarcity are delineating the limits of mobility. Now the question is: How can we organize mobility intelligently such that it creates value for our customers according to their personal needs?

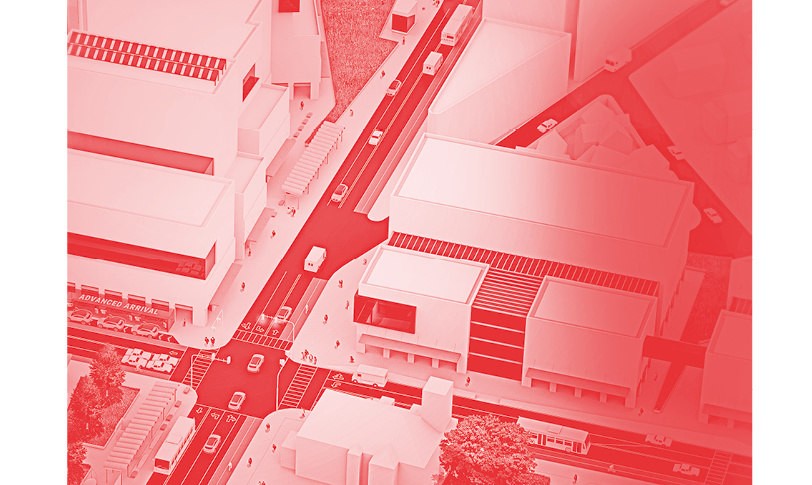

We see the car as part of the solution, not part of the problem. Audi is testing swarm technologies, self-parking cars and connected traffic lights, for example, as ways to optimize traffic flow and simplify the search for parking. But you have to understand how people behave in cities. Everyone needs to take part in this: Urban planners, architects, politicians, researchers and carmakers have to work together to create smart concepts for using the available space in cities more efficiently. No one is efficient enough in their own sphere of action—but by working together, they can achieve a lot.

The long-term goal at Audi is to become a zero-emissions brand. By 2025, Audi will offer more than 20 electric models—almost half of them plug-in hybrids and the remainder purely battery powered.

Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands, is a pioneering metropolis when it comes to advancing electric mobility. As far back as 2009, the city installed the first public charging stations for electric vehicles. By 2016, there were already over 2,000 of them. Today, Amsterdam boasts the world’s densest network of charging points. What’s more, the alderpersons have decided that not only the city’s entire vehicle fleet but all taxis, too, must be entirely emissions free by 2025. In 2018, the introduction of an environmental zone for taxis will ban those with the worst ecological footprint from the city.

The size of parking spots for self-parking cars is roughly two square meters smaller than for cars parked by people. With the same amount of floor space, a parking garage can therefore accommodate 60 percent more cars if all of them are self-parking.

Audi and the town of Somerville north of Boston in the U.S. have been working on urban mobility solutions for tomorrow’s cities since 2015. Aspart of the process, the brand with the four rings is harnessing innovative technologies, such as networking vehicles and infrastructure as well as shared mobility solutions.

Mark Simon of the New York City Department of Transportation says, “We don’t want more cars in the city; we want more bike paths, more green areas, more space for pedestrians.” Will city dwellers need to part with their private cars?

Van De Weijer: If you live in the center of a city, you may need to accept the idea that this fact doesn’t automatically require you to own a car. But that doesn’t mean you can’t use one. So many different services are springing up that enable car use without car ownership. Yet the trend is clear: Cities are re-zoning space that used to be reserved for mobility so people feel good about being there. The High Line in New York, which used to be train tracks and has now been turned into a park, is just one example. Today’s cities are moving away from allotting 40 percent of their space to traffic.

What will that mean for Audi if tomorrow’s mobility not only gets less space but also results in less ownership?

Schot: I am sure that mobility will become more and more of an individuality factor. The premium experience is still key for Audi customers. But autonomous driving will fundamentally change society, the role of cars and our mobility behavior going forward. A new kind of individual traffic using robot taxis might be an option, for example. That can potentially make traffic more efficient by maximizing vehicle capacity utilization. At the same time, it would require less space for parking and reduce the time each car spends idle. Why should cars only be used for 30 percent of their service life? They could also be used for 70 percent of that time. That will spawn new business models in the future. Maybe down the road Audi will also sell kilometers driven per hour.

Van De Weijer: Whenever new concepts like this are emerging, people tend to use cars more, not less. The services now being created do not pose a threat to car manufacturers’ business; in fact, they will mean even more business.

Is automated traffic the golden path to tomorrow’s urban development?

Schot: There will be more transportation options. For instance, when I want to go from the center of Amsterdam to Schiphol Airport on a Monday morning, I will be able to choose between a taxi, an Uber or a robot taxi. But using a shared car does not entirely satisfy my individual needs if, for instance, what I really want is to own an Audi RS 6 Avant** or a convertible. The new usage models make mobility more efficient with more passengers per car, so overall there will be fewer vehicles driving around on the streets. Increased effectiveness also spells freer traffic flows. And that in turn can mean more fun for me behind the wheel of my Audi RS 6 Avant**.

Mr. van de Weijer, you predicted in a recent lecture: “This development will also increase traffic, because autonomous cars are convenient and safe.”

Van De Weijer: Yes, I’m afraid tomorrow’s driverless vehicles will not really solve the problem in cities. Many say driverless cars will transport more people per vehicle. I don’t really see it that way, because cars will also be driving around without passengers. So the average number of people transported per car will actually even drop. Even if four people used one car, that would not reduce the number of vehicles enough for our urban centers. Tomorrow’s cities don’t need driverless cars; they need carless drivers.

In Amsterdam, 31 percent of commutes are undertaken by bicycle. The network of cycle lanes is 600 kilometers long and 80 percent of residents own at least one bike. In fact, there are apparently more bicycles than people in the city. Is this a direction we should pursue with future traffic concepts?

Van De Weijer: It all comes down to what is known as corridor capacity: In other words, how many people can pass through a 3.5-meter-wide corridor into a city within an hour? The figure 3.5 meters is the average width required for a street or train track. Today, the corridor capacity for cars is about 1,000 people. If you put four people in each car, it rises to 4,000. In autonomous cars that run like trains, that number could even go up to 5,000. But that’s not enough. A public transport system, such as buses, achieves roughly 10,000 people per hour, while subways push 25,000. The surprising thing is that a cycle lane has a corridor capacity of up to 15,000, which is why bicycles are enjoying a boom as a mode of transport in urban areas. After all, cities need to put some thought into optimizing corridor capacity. How much space do they need to be able to transport a specific number of people into a city? The answer determines what is the most suitable mode of mass transport. That’s why I keep driving home the point that instead of driverless cars, I want to see drivers without cars.

The native of the Netherlands is a father of two sons—“one of them a gearhead, the other not especially enthusiastic about cars”—and is the member of the Board of Management of AUDI AG responsible for Sales and Marketing. He sees far too little of his home town, Amsterdam, where he likes to live in the city center. With all the traveling he has to do for work, he’s already really looking forward to tomorrow’s premium self-driving cars.

Founded and owned by Audi, Autonomous Intelligent Driving GmbH is currently working with its parent company to develop suitable technology for robot taxis.

A thought leader on mobility, van de Weijer not only conducts research as Director of the Strategic Area Smart Mobility at Eindhoven University of Technology but also heads up R&D at a leading global provider of navigation solutions in addition to advising governments, industry associations and businesses around the world on the future of technology and mobility. He has driven an electric car for the past five years but traveled to the interview by train and a rented bicycle.

Schot: Even so, autonomous driving will have a huge impact on how cars are perceived. At present, the car is just a mode of transport. You get behind the wheel and, while you’re there, the only thing you can do is converse with a passenger, drive wherever you’re going and park the car. From that moment, the car becomes an inefficient object, because it’s just sitting there unused. Instead, it could autonomously drive off to the school to fetch the kids. Or I could use it to hold a video conference with colleagues or have a twelve-minute power nap. That would make it far more efficient. The car would become part of my life and make it more streamlined and pleasant. When, in the future, I can finally do all the things in a car that I couldn’t do before, then travel ceases to be an obstacle. And there’s nothing to stop you using a car. On the contrary, tomorrow’s cars will become the new living space. People will spend more time and have more control over what they do in cars.

Van De Weijer: Autonomous cars are not going to put an end to congestion over the next decade. But people won’t care that they create bottlenecks because they can work during a journey in a self-driving car. By the same token, this would, however, alleviate the enormous economic impact of gridlock without actually preventing the jams themselves. If bottlenecks no longer bother people much, it becomes possible to resolve the traffic jam problem without eliminating it. An upshot may be the ability to schedule congestion, which, for logistical reasons, would be a win.

Does that mean you agree with Bram Schot that swarm intelligence and autonomous driving will make tomorrow’s cars more attractive?

Van De Weijer: Yes, these are the forms of intelligence that spur a surge in quality. If gridlock is no longer a headache, then car journeys are much more pleasant. As a rule, people don’t want to waste their time in traffic, get into accidents, search for parking or have to park the car themselves. These are all inconveniences that new technologies can banish from our lives. And when the unpleasant aspects of driving disappear, then driving becomes all the better for it. I like to compare it to skiing. The sport became popular when lifts took the bother out of getting back up to the top of the slope. Which is exactly what’s now happening with automation in mobility. It’s not about driverless cars or robot taxis. It’s about getting rid of what’s tiresome about driving and replacing it with a higher quality experience.

Do you see electric drives contributing to this increase in quality?

Van De Weijer: Absolutely. Electric mobility will be clean and affordable—it’s the next logical step toward the future. Electric cars last longer and require less maintenance than vehicles with combustion engines—they’re the more economical choice. I was very skeptical before I bought my own electric car. Now, I know that a range of 400 kilometers is sufficient. I start my day with a fully charged battery and very rarely need a speed charger. When that occasionally happens—less than once a month—it’s not a problem because I’ve already taken the half hour of charging into account when planning for a longer journey. And rather than sitting around waiting during that time, I work in the car or eat lunch. If you prepare for it, this charging time is surprisingly enjoyable and just takes one neat click. Filling up the tank in a car with a combustion engine, you have to stick a nozzle to direct the flow of fuel into the car for three minutes. Just thinking of those three minutes annoys me.

Schot: Once charging is possible whenever and wherever, that will be a huge draw for electric cars. We talk to a lot of customers and many are still unnecessarily concerned about having to make compromises with an electric drive. It’s a very interesting debate, because average drivers in Europe tend to cover 28 to 30 kilometers per day. So this isn’t about whether a car has a range of 400 or 500 kilometers. The key questions are where can the car be charged, and how fast. I sincerely believe that by as early as 2025, electric cars will account for 30 to 40 percent of cars on roads around the world. At Audi, we have also committed to ensuring that one in every three cars sold is electric. My experience is that people who own an electric car are very happy with it.

Don’t the anticipated leaps forward in battery technology also put customers off buying an electric car today?

Van de Weijer: It’s the same problem as holding out for an even better computer. You end up never buying one at all. At some point, you just have to get on board with the technology. I’ve been driving an electric car for almost five years now. And the battery capacity is still at over 90 percent. The capacity loss is nowhere near what most predicted. Off the showroom floor it had a range of 400 kilometers, while today that’s 378 kilometers. So that really isn’t a problem.

A key requirement for the future of electric mobility is a well developed charging infrastructure. This is why Audi has joined with partners to form the joint venture IONITY. The company aims to build Europe’s top performing fast-charging network for electric vehicles.By 2020, some 400 IONITY fast-charging stations will be available.

Facts & Figures

Amsterdam

Further photo credits: AUDI AG, Autonomous Intelligent Driving, IONITY

** Audi RS 6 Avant fuel consumption urban/extra-urban/combined (in l/100 km): 13.4/7.4/9.6. CO2 emissions combined (in g/km): 223.

* In the meantime, Bram Schot has additionally assumed the role of acting Chairman of the Board of Management of AUDI AG.