The Highways

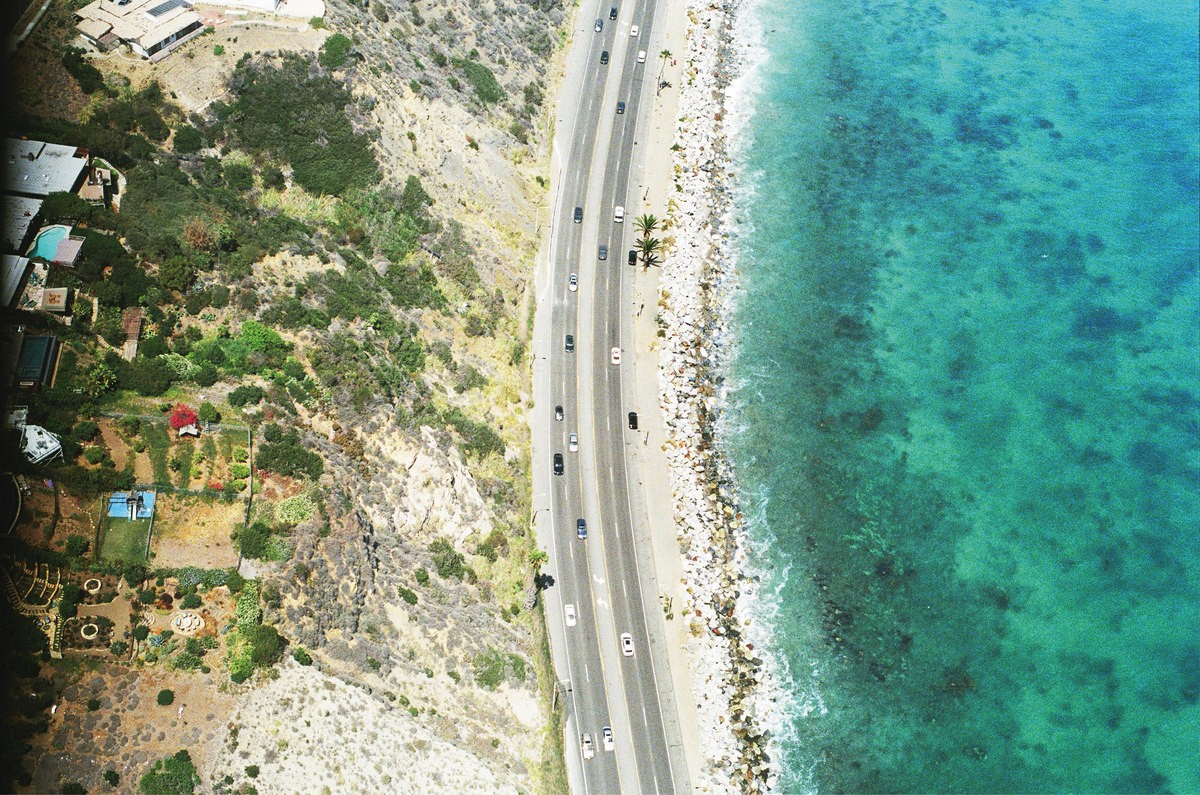

When driving becomes more and more data driven, what will be left of the rebel roads of our youth?

Angus Frazer (interview), Ryan Brabazon (photo) & Constanze Saemann/Oui Management (model)

Back in the 1920s, late one moonlit summer’s night, my grandfather was driving his horse and cart home through the Ulster countryside when he fell asleep. He’d spent a long day in the fields, so the fact that he nodded off to the rhythm of the horse’s hooves was no great surprise. Nor was it a problem, for the horse knew the way home and transported my grandfather safely to his own farmyard. I sometimes wonder what my grandfather would think of the world today, when you consider just how much has changed in the past century. Back in the 1920s, cars were still a very rare sight on rural roads in Ireland.

Level 1: Cruise control regulates both the speed and the distance to the vehicle in front. The driver must always hold the steering wheel and pay attention to traffic. The systems are, however, restricted in their functionality. They do not work properly in bad weather conditions, for example, and can only be used up to a certain speed.

There is a difference between piloted driving and autonomous driving. In fact, it is like cats and dogs. While piloted, you still can drive by yourself. Once autonomous, all driving is done by intelligent machines. There are five steps in total.

Today, there are an estimated 1.2 billion cars of incredible variety on the planet. Yet they all have one thing in common, and not just with each other, but with every automobile ever built. No car will move a millimeter without the interaction of a human being. A handful of experimental self-driving or autonomous cars of course prove the exception to this rule, but few of us have seen them in the metal. For now, unless you happen to live in an area where they are tested, they are a much rarer sight than an automobile would have been in my grandfather’s youth. Yet some automotive industry observers estimate that there could be 10 million self-driving cars on our roads by 2025, many of which will be capable of driving their occupants home should they fall asleep. Today, that seems almost unbelievable. Indeed, to some people it may seem as likely to happen as the idea of the automobile one day completely replacing the horse would have seemed to my grandfather when he was a young boy. Yet before we think ourselves oh-so-clever and sophisticated, we should realize that we, too, are using machines in our daily lives that will one day, in the not too far distant future, be regarded as antiquities. The other day, I was walking around a huge, state-of-the-art car showroom, full of modern technological wonders, albeit all of them equipped with a steering wheel, with a friend and his one-and-a-half-year-old son in his push chair. “Brrm! Brrm! Brrm!” came the excited cries as the little boy’s sticky fingers reached out to touch the tantalizingly close gleaming metal—reaching out, it seemed, to touch the future. And yet it is not going to be the future, for by the time he is old enough, cars will probably be equipped with a high level of autonomy, if indeed they are not completely autonomous. Like it or not, that modern car showroom is already a museum.

Level 2: In certain situations such as on motorways, the car can perform certain functions autonomously, such as driving straight ahead, staying in lane and maintaining the distance to the vehicle ahead. In traffic jams, the vehicle takes over completely if the driver wants it to. Again, responsibility for the control of the car fully remains fully in the hands of the driver, who can take charge at any time.

In just a few months, the cars in Audi Centers will be joined by the all-new Audi A8. This is the first production car in the world to have been developed specially for highly automated driving (Level 3, as it is called). At the touch of a button it will be capable of taking charge of driving in certain situations with the possibility for the driver to take back full control. There is no doubt that as such autonomy increases it will bring huge benefits. Things are going to change and they are going to change fast. But how will this autonomy change our emotional responses to cars? Will the car just become another domestic appliance, generating little more desirability than a cooker or a washing machine? And how will we even talk about cars? After all, asking each other “What do you drive?” will become completely redundant. One wonders what we shall ask instead, if indeed we still find the question interesting enough to ask. What drives you? What are you driven in? Will little boys—I know sometimes it is little girls, too—still go “Brrm! Brrm! Brm!” when our roads are filled with self-driving, silent electric or hydrogen powered cars? After “Mummy” and “Daddy” the first word my oldest nephew uttered was “digger.” When my second nephew came along, he was just as fascinated by anything with an engine. He used to love sitting on my knee in a parked car grappling with the steering wheel, until he worked out that he needed to get the key out of my pocket. Obviously, I never let him have it, but not all guardians are as careful.

Recently in West Virginia in the United States, two young brothers, aged two and five, managed to get the keys to their mother’s car. They promptly set off along a windy country road, one operating the steering wheel and the other the pedals. They made it three miles (4.8 kilometers) before crashing into a ditch, happily without injury. I had to wait a little longer before I got behind the wheel, although I waited not one single second longer than I had to. On the night before my seventeenth birthday, I persuaded my uncle to drive to my parents’ house, leave his car there and then drive the van my father used for his garage business to my uncle’s house with me in the passenger seat. We stayed there until the clock struck midnight and I turned seventeen, the legal age to drive in the UK when accompanied by an adult license-holder, and then off we set, only this time with me behind the wheel. And was there ever such a drive? The run through the pitch-black country lanes burns bright in my memory like it was last night, not thirty years ago. I’ve been very lucky for someone who grew up going “Brrm! Brrm! Brrm!” I’ve got to write about cars for a living and driven many an Audi, Bugatti, Bentley, Ferrari, Lamborghini, Porsche and the like in many exotic locations all over the world. And yet sometimes I wonder if there was ever a moment that equaled the sheer physical and emotional thrill of that very first time.

Level 3: The systems can take over the journey almost completely, especially on highways, including passing and swerving out of the way. After a warning period of several seconds, the driver is asked to take over the steering wheel again. Despite the high degree of automation, the driver has to keep track of the events on the road the entire time in order to be able to intervene if necessary.

People like to ask, “What’s the best car you’ve ever driven?”

But really the question is: “What’s the best road you have ever driven on?”

Level 4: This is the big leap that is expected by 2020 or 2022. The car drives on its own most of the time. It parks independently. It drives by itself on country roads and in the city. Drivers can devote themselves to other things and do not have to keep an eye on the traffic all the time.

But will young people still yearn to get behind the wheel, when there is no longer a wheel to get behind? And what will be the legal age at which one is able to take control of a vehicle when in fact it is the vehicle that is in control? When I was younger, I would have dreaded a world where cars take control, but as I get older, even though I still love the act of driving just as much as ever, I feel my views changing. Having seen too many accidents, I know that the huge benefits in safety that autonomous driving will bring can only be a good thing. Now, as my nephews take to the road as young drivers, I would be quite happy if the cars they will be driving were equipped with some level of autonomy to keep them safe, and to prevent them doing all the silly things I did in a car when I was eighteen. I dearly wish my parents owned a fully autonomous car too, to make traveling less stressful for them. But do I want one? Not now, if I am honest. Yes, there are plenty of times when I am stuck in horrible traffic that I would dearly love the car to do the driving, but most of the time I get too much enjoyment from the physical sensation of driving. After a long, stressful day at my desk, the last thing I want to do is spend more time checking emails while the car does the driving. On many occasions, especially if I have not been behind the wheel for several days, it is the actual act of driving that helps me unwind. Get in the car, switch the phone off, switch the radio off, switch the whole world off and just concentrate on every gear change, every accelerator and brake input and every turn of the steering wheel—for me, that’s where the pleasure is. So one day, yes, definitely, I would like an autonomous car, but not just quite yet thank you.

Of course, all this assumes that we will still own cars in the future, which will almost certainly not be the case. Cars are more likely to arrive summonsed only when we need them. But some of us may still choose mechanized monogamy as opposed to an endless series of unfulfilling automotive one night stands. And those of us who give our cars names, for example, might be teetering on the edge of a whole new level of automotive emotional attachment, and not just because of cars’ ability to drive themselves, but because of the level of artificial intelligence that will come with full Level 5 autonomous driving. What a nice vision of the future.

The other day, I was listening to a radio play, a modern interpretation of Isaac Asimov’s ‘I, Robot’. The heroine was having a conversation with her self-driving car. “Have I got time for a coffee before my next meeting?” she asked. The car replied, “Yes, certainly, your next appointment isn’t until 15:00 and I could do with a quick charge while you are having your coffee.” What was interesting to think about was the relationship the heroine was having with her car; it was almost as if they were looking out for each other, the driver getting a coffee and the car an electric charge. Audi is convinced that the car will play an important role as a personal assistant, and this function will surely only increase dramatically as cars become ever more intelligent, until they become our confidants, our friends. But can you imagine the terrible day when you have to tell the car to drive itself back to the dealership because its replacement is on the way? It would be more tear-jerking than a scene from the film ‘Lassie’. Life could also get tricky in other ways, too. Even today I have to be careful on long trips with a normal car. That’s why I always let my partner take the wheel for the first part of the trip, and then I will take over for the second part after lunch. About 15:30 I always suggest we stop for tea and cake. Miriam always makes the argument that I have had a perfectly fine lunch and that it is much better just to keep going. But, as I am in charge of the vehicle, I pull over into the next motorway restaurant. However, with a fully autonomous car I will have no chance. The car will take my partner’s side, every time. On we will whizz, past motorway restaurant after motorway restaurant, getting to our destination faster and living a healthy lifestyle—but without any tea and cake for me.

The way I remember my grandmother, I am sure she would have tried to control my grandfather in a similar fashion, but knowing my grandfather, he would have just ignored her and done as he pleased. And he would have got away with it, because despite my grandmother’s many talents, not even she could give a horse instructions. But maybe technology will work out for me in the end, because when you stop to think about driving, you realize that the pleasure of driving is in the road and in the journey, just as much as it is in the car. People like to ask, “What’s the best car you’ve ever driven?” but really the question is “What’s the best road you have ever driven on?” If I had the choice, I would rather drive a compact car along the Atlantic Road in Norway under the midnight sun than be stuck in a supercar for hour after hour in city traffic. Because let’s face it, that’s what the car has always been about: freedom. I know that, you know that and those two little boys in West Virginia know it, too. The car gives us the chance to break away from everyone else, to go where we want, to do what we want and to be just a little bit of a rebel. If we are lucky and live a long and healthy life, we can keep enjoying that freedom for many, many years. But eventually there will come a day when our reactions are too slow, our eyes too poor or our nerves too frayed to drive a car on our increasingly busy roads. Some countries are already looking at the idea of forcing drivers over a certain age to take their driving tests again, and if they fail, that’s it—no more breaking away, no more freedom, no more rebellion. But perhaps in the future, as long as we still have a breath of air left in our lungs, we may never have to surrender that freedom, not if the car is doing the driving for us. No matter how old we get, autonomous cars will enable us to roam the half-forgotten rebel roads of our youth once again.

Facts & Figures

Autonomous driving

Level 5: From this point, cars will no longer be equipped with a steering wheel. Then the time has come for the “25th Hour,” which is how Audi envisions drivers using their time in the car when the task of driving has ceased to exist. This could become a reality around 2025.