Electrifying future

Always a bit more advanced: No other city in the world has faster Internet or is as connected as South Korea’s capital.

Fabian Kretschmer (copy) & Julian Baumann (photo), Raymond Biesinger (illustration)

If you want to understand the Han River miracle, go to Gangnam—the upscale business district in Seoul that skyrocketed to worldwide fame through the YouTube hit “Gangnam Style” by K-pop singer Psy. Here, where rice fields, oxcarts and farmers’ shacks dominated the landscape as recently as the 1970s, 14-lane highways are now flanked by neon-lit office towers. The majority of Korean corporations have settled in Gangnam, along with ultra-elite high schools, the ritziest night clubs and the most exclusive designer boutiques. Nowhere is the Koreans’ uncompromising will to get ahead more visible than in these nearly 40 square kilometers of cement and glass facades. So it was no accident that the Internet giant Google also chose this spot for its first campus in all of Asia three years ago.

“Innovative thinking is deeply rooted in the culture.”

Michael Kim, at 34 already a tech veteran with a decade in Silicon Valley under his belt, receives us in his sunlight-suffused offices that boast all the classic insignia of a California startup: an industrial-garage look with an open floor plan, the compulsory foosball tables, an integrated café. Twenty-somethings with open laptops nurse lattes at wooden tables; their T-shirts, jeans and sneakers are a stark contrast to Korean companies’ conservative dress code. The country’s cleverest young entrepreneurs are busy working on apps and startups here. To hear Kim tell it, Google’s decision to set up shop in Seoul sounds like the only logical course of action: “When you look at what makes startups successful around the world, you need three things: talent, infrastructure and a certain company culture. We have all those things here in spades.” A glance at the statistics shows that the Google manager is right: At just under 70 percent, South Korea has the highest rate of university graduates of all OECD countries, and the most common studies consistently give its education system top marks internationally. “Innovative thinking is deeply rooted in this people’s culture,” Kim says. “Many of the most brilliant ideas originated in Seoul, not Silicon Valley.” In 1999, five years before Facebook was founded, Korean engineers launched Cyworld, the planet’s first social network. And before YouTube revolutionized our movie-consumption behavior, Koreans could already stream videos on Pandora TV. “Korea is always a step ahead of the zeitgeist. People think about the future constantly,” the Google manager says. “Everything has to move fast here: If you want to establish a new startup hub in Seoul—including a subway line to the center of the city—it will spring up in four months.”

For Michael Kim, APAC partnerships manager at Google for Entrepreneurs, Seoul is more than just a stop on his career trajectory. A native of the U.S., he wants to spend the rest of his life in the South Korean capital. This choice is also a journey to the cultural roots of his parents, who emigrated from Seoul to San Francisco long ago.

Just five months after its release in July 2012, the K-pop song “Gangnam Style” reached one billion views. It remained the most viewed video in YouTube’s history until the middle of 2017.

Seoul’s subway system is buried deep underground; many of its tunnels could be used as fallout shelters in the event of a nuclear incident with North Korea. Internet service is nonetheless always available. Most commuters spend their trip to the office online.

THE WORLD'S FASTEST INTERNET.

Angie Cho, head of an online marketing agency and tech columnist, has long embraced fancy digital gadgetry as part of her everyday life. Whenever she goes abroad, she feels as if she has traveled back in time to the analog past: slow Internet, scarce Wi-Fi hotspots.

A glass fiber is just barely thicker than a human hair but it offers incredible performance. Glass fibers conduct data via light waves. They can carry more data per unit of time than electricity is able to.

Undoubtedly, South Korea has undergone a more profound transformation with-in the space of one generation than has been achieved in any other country; as recently as the 1960s, the bitterly poor agricultural state lay in ruins, its GDP on a par with that of Ghana or Afghanistan. Since then, the Asian nation has ballooned into the eleventh largest economy on the planet. South Korea has also long been a trendsetter for East Asia and beyond: K-pop bands sell out stadiums from Beijing to Manila, Korean TV series are featured on prime time TV in Iran, and Berlin hipsters pickle their own homemade kimchi. The backbone of South Korea’s economy is certainly its digital supremacy.

This was built on massive government investments. All the way back in 1995, South Korea’s government created a ten-year plan to expand broadband Internet, used publicity campaigns to generate acceptance for it and eased restrictions on the market for Internet providers. This strategic investment soon paid off: South Korea now boasts the world’s fastest Internet by far, which, with an average of 28.6 megabits per second, is twice as fast as Germany’s. The next milestone came in 2015, when the Ministry of Science announced a 1.5 billion euro investment package designed to expand the country’s mobile infrastructure by 2020. Wi-Fi has long been available in 95 percent of the country.

Pangyo Techno Valley is located around 20 kilometers south of Seoul. Its glass buildings arranged in a chessboard pattern, interspersed with landscaped green spaces and brooks along with pristine sidewalks and barely used streets, lend the complex a utopian feel. Eight years ago, Seoul’s government started luring young tech companies to the outskirts of the city with tax breaks. Since then, the local version of Silicon Valley has emerged on 661,000 square meters of real estate in Pangyo. Tim Spaninks, a Dutchman with a navy polo shirt, designer jeans and aviator sunglasses, has called Pangyo Techno Valley home for over a year. A tech wunderkind, he started building his own levels for computer games while he was still in elementary school. When he finished university in Finland, the game designer joined with some friends to set up their own company: eight people with 200,000 euros in seed money, financed through loans from relatives. Critical Force was the name the developers chose for their venture. Their signature creation is a first-person shooter game for mobile devices that has now been downloaded over 40 million times. “But it was obvious to us that we had to put a Korean version on the market—and to do that, we needed a branch in Seoul. If our game works in Korea, it can be a hit all over the world,” Spaninks says. With 25 million people in its metropolitan area, Seoul is considered a test lab for game developers: “Seoul is the key to the Asian market. In China and especially Southeast Asia, the scene looks to South Korea first.” Critical Force targets the eSports market, i.e. online gaming as a competitive high-performance sport.

Tim Spaninks

“South Korea’s eSports dominance hinges on Internet speed. After all, the difference between victory and defeat is often mere milliseconds.”

Seoul is indisputably the world’s top eSports mecca. An industry worth millions has evolved here over the course of more than a decade—with pro gamers who train seven days a week in team camps, purpose-built eSports stadiums that draw thousands of fans cheering for their heroes on weekends, and sponsors that put up six-figure prizes. “South Korea’s eSports dominance hinges on Internet speed. After all, the difference between victory and defeat is often mere milliseconds,” 26-year-old Spaninks says. Whether they’re in the subway tunnels deep underground or on the peak of 1,950-meter Mount Hallasan, South Korean gamers always have the fastest Internet connections.

We take the subway back to the center of town, gain access to the platform with a smart card and, for the first time, witness the digital side effects of the country’s high-tech society: Weary commuters fix their rapt gazes on oversized smartphone screens; every single passenger is online. The smombies keep at it even while switching trains. Feet dragging, faces glued to their phones, the passengers shuffle along from A to B. When we get off at the centrally-located Gwanghwamun Square, analog life has caught up with us: Union leaders with red headbands demonstrate loudly against announced layoffs, a self-anointed messiah with a red wooden cross on his shoulders warns of the imminent apocalypse, while old women in outsized visors insistently distribute flyers for neighborhood restaurants. Scooter messengers bearing meal boxes race through the side streets to the nearby offices—in Seoul, even lunch is managed with an app. The headquarters of KT, South Korea’s leading telecommunications provider, looks from the outside like a stark functional structure in faded ocher. Inside, however, it opens a window on the future. Hyung-joon Kim welcomes us for our interview in an oval showroom which, with its LED floor, could double as a sci-fi movie set. Virtual reality headsets hang on the walls, and downtown Seoul, in mini-hologram form, sprouts from a console in the middle of the room. Hyung-joon Kim is KT’s vice president in charge of global operations. Kim, whose background is in banking, wants to give us an idea of the next generation of mobile networks: 5G is the magic word, and he says it will revolutionize our everyday lives. “We tried out the first 5G test network during the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang in February. Based on that, we introduced completely new kinds of services for the audiences,” Kim says. Such as Interactive Time Slice: With ski jumping, KT installed a total of 100 cameras whose image data melded into a revolutionary TV experience. When the jumper lifts off, the user can not only change the image detail on the touch screen but also rotate the angle 360 degrees—in real time, with no delay.

Seoul has long since evolved into an international startup hub. The young team at Rocky Robots is working on a model designed to use artificial intelligence to act as a personal trainer. East Asians accept new technologies far more readily than Europeans do.

In Reutlingen, Germany, a sign warns of “smombies” (smartphone zombies). But this is not an official traffic sign. No one knows who designed and installed it.

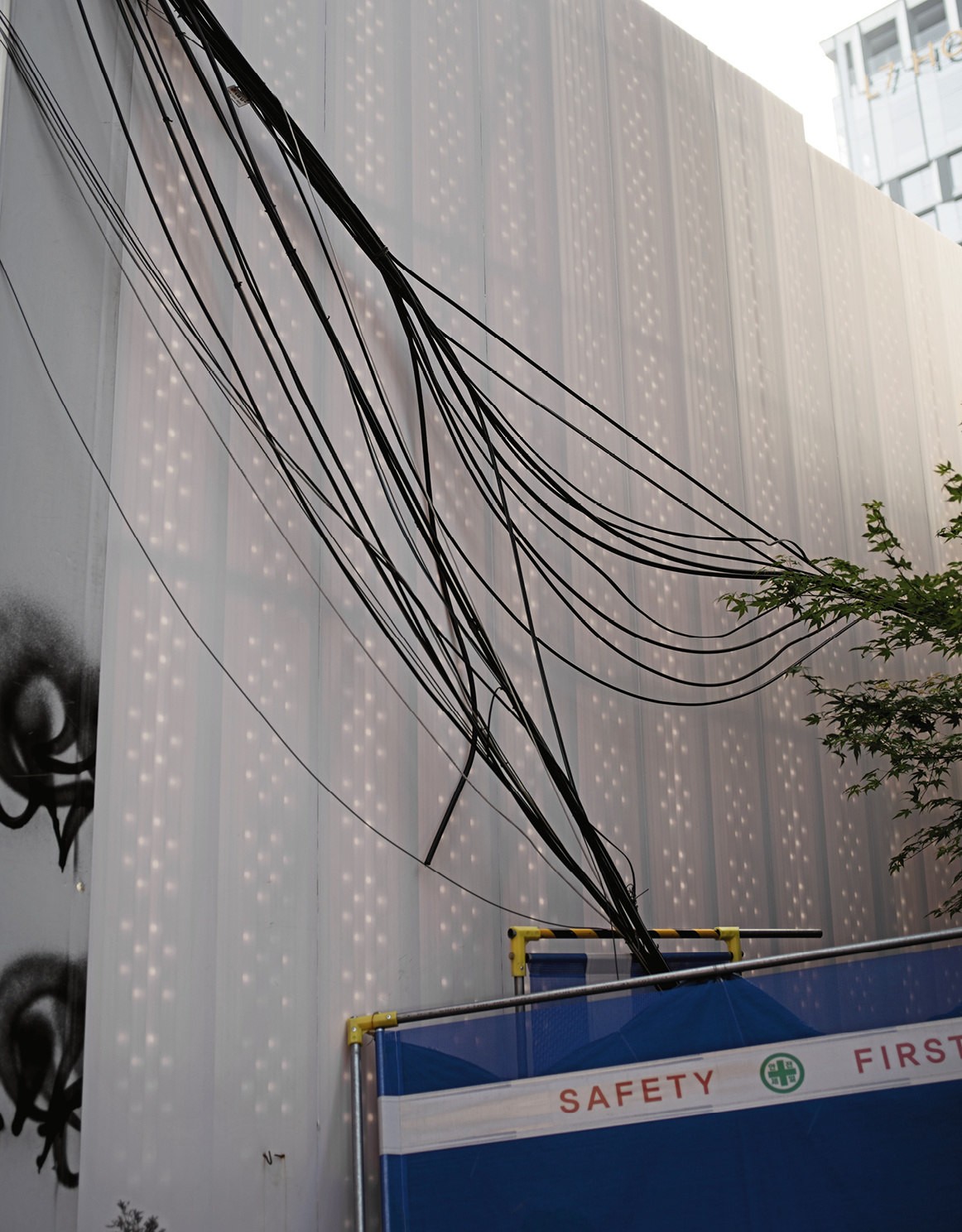

In even the most modern of Seoul’s neighborhoods, free-hanging fiber-optic cables bring the Internet into people’s homes. But don’t let looks deceive you: South Korea boasts the world’s fastest Internet, averaging 28.6 megabits per second.

Glass fiber has long been used to create art as well. Eva Hesse experimented with fiberglass asa new material way back in the 1960s. Her works are shown at the MoMA in New York, among other venues.

“5G is 20 times faster than the current LTE technology,” Hyung-joon Kim says. “In the future, you’ll be able to load 20-gigabyte video files in one second. And the lag time is less than one millisecond. So data can be sent and received from various locations with virtually no delay.” That would enable autonomous vehicles to be commercialized on a massive scale. And drone technology to be used better: In the future, if a fire starts—at least this is the idea—a fire truck would soon no longer have to muscle its way through the rush-hour traffic. Drones would be dispatched to the scene of the accident automatically to put the fire out. “5G will be the backbone of the fourth industrial revolution—and will play a similarly pivotal role to that of steam engines or electricity back in the day,” Kim says with conviction. In the first quarter of 2019, KT aims to launch the 5G network nationwide—and be the world’s first telecommunications provider to do so. Before taking leave, we ask why Kim thinks his countrymen and women embrace technology so eagerly. “We have to rely on our human resources; after all, we don’t have any natural resources. That also means that we have to adapt constantly—even just to keep up with the world’s top economies.”

This adaptability is also reflected in the architecture of Seoul City Hall, a futuristically curving glass structure in the shape of a gigantic wave. After signing a confidentiality agreement, we head down to the third floor below ground—and land promptly in a nuclear fallout shelter. Unwittingly we are reminded of the conflict with North Korea, whose border is just an hour’s drive from here. Should Kim Jong-un ever threaten the center of Seoul with nuclear warheads, government officials would find refuge in the City Hall basements. Around 110 people could survive here for a month and a half. But in peacetime, these rooms function as the logistics linchpin for the metropolitan area with its population of 25 million: The Seoul Transportation Information Center uses big data to manage transportation throughout the city down to the finest detail, prevent weather damage and keep residents safe—all with just a touchscreen.

Youn-gye Yang

Youn-gye Yang heads the Seoul city government’s Transportation Information Center. In his control room, he uses big data to manage all the traffic and transportation in the entire city. The metropolis of ten million has 813 closed-circuit cameras watching over it. Most of the data they provide is available to the public free of charge.

Youn-gye Yang, the manager, an enthusiastic older gentleman with twinkling eyes, proudly displays the tablet he uses to predict floods during the rainy season, send out heat warnings to the populace in summer or turn on the heating that melts the ice on the streets in the winter. Yang’s command center consists of a 20-meter-wide screen and several dozen computer workstations. On this particular afternoon, however, only two workers are on duty, tweeting out information about accidents and detours.

“When I was growing up, Seoul’s streets were so congested that a drive through town often turned into a day-long excursion,” the city employee says. Seoul didn’t build its first train station until 1971; today, the city’s metropolitan railway system, with 23 commuter lines and over seven million passengers a day, ranks among the most effective on the planet. It is the beating heart of the South Korean capital’s transportation system. Youn-gye Yang pulls out his tablet again and projects a grid of the city onto the giant screen. “Depending on the average traffic speeds, the color changes.I can see within one kilometer per hour how fast things are moving.” With the euphoria of a teenager who has just discovered the computer game Sim City, he demonstrates with a few keystrokes all the gimmicks his console offers: how many taxis are currently driving passengers (23,566), the number of buses that are speeding (92) or whether he forgot to close his living room window (no); 813 closed-circuit cameras with integrated super zoom features let Yang peek into virtually any nook or cranny in the entire metropolitan region.

Our final evening of research is spent with Angie Cho. At a coffee house, over espresso and cookies, she recounts her career as one of the first women early adopters in the male-dominated tech industry. Her main job is running an online marketing agency, but she also moonlights as a columnist writing about the latest digital gadgets. “People in Seoul spend more time at the office than virtually anyone else in the world. Free time is scarce. Digital technology helps them make their lives healthier, easier and more efficient,” Cho says. During our interview, she wears a baseball cap that features integrated, invisible Bluetooth earphones. On the table lies an ordinary-looking notebook with a pen. But the pen is equipped with a camera that transposes handwriting straight into her tablet’s e-mail program. The best Internet products, in Angie Cho’s opinion, couple digital convenience with the feel of the analog world: “Whenever I’m in Europe on vacation, I am fascinated to see that people integrate very little technology into their everyday lives. But after the first day, I miss the speed and tech convenience of Seoul again.”

Seoul’s subway network is considered one of the most efficient public transportation systems on the planet. It moves over seven million passengers every day. The fare costs the equivalent of just one euro, and is paid electronically with a smart card.

Further photo credits: Schoolboy / Universal Republic Records, NoiseD / Wikimedia Commons, Christoph Schmidt / dpa / picture alliance