Welcome to the society of the future

In no other city in the world are people as thoroughly digitally-minded as in Tallinn, Estonia. How does that change a society?

Dirk Böttcher/Lea-Marie Kenzler (copy) & Matthias Ziegler (photo), Raymond Biesinger (illustration)

The first step in learning something about digitalization in Tallinn was going to Ecuador. We skyped Marten Kaevats in his hotel room in Quito. Everyone had told us he was the man to talk to. In the 1990s, Kaevats was a cycling proponent and an activist in the broadest sense. Trained in architecture and urban planning, he introduces himself as a “circus bear.” Sporting tousled hair and a faded T-shirt, Marten Kaevats looks like a singer in a punk band—and not much like a National Digital Adviser. Kaevats works for the Estonian government as a consultant on digital issues. By invitation of the Asociación Latinoamericana de Exportadores de Servicios, he is today going to speak to an elite group of members of the Latin American service provider community in Quito about digital services. Digitalization is Estonia’s most important export hit and its only blockbuster.

Since the 1990s, this diminutive country with just 1.3 million inhabitants has systematically pursued a digitalization strategy. Its stature in cyberspace has long since surpassed its physical boundaries. Kaevats calls the substance of his work “the cool stuff,” which in his view mainly refers to public administration. In this story, we will meet a number of characters like Marten Kaevats and get to know a city so immersed in the digital world that many things still being debated elsewhere have long since become old hat in Tallinn. People there are working on things others haven’t even thought of yet. Whereas other nations are starting to put forms online for their citizens, Tallinn is getting rid of the concept of submitting forms altogether. “In the future, we will put big data and artificial intelligence to work to save citizens the time they spend filling out forms,” says Kaevats. “Our systems independently identify who is eligible to receive a child subsidy, for example. Ten minutes after the birth of their child, parents receive an email congratulating them and specifying the amount that will be transferred to them and when.”

Tallinn in November—first snow. Towers with glass facades stretch toward the sky; a picturesque old town crouches at their feet. People hurry along the sidewalks—at first glance, we don’t notice anything special in the capital of cyberspace. Kaevats had told us that digital services are primarily at work where they are not readily visible. In a way, they are only evident in the countless bureaucratic trips people no longer have to make because they don’t need to take documents to government offices or banks. “Digitalization,” states Kaevats, “gives people their freedom back so they can do what they want.” Our attempt to make the virtual world in Tallinn tangible takes us to the e-Estonia showroom. We wait on a blue couch to be picked up by our tour guide. A door suddenly opens up in a nondescript wall, and Federico Plantera, spokesman and media representative, enters the room with a smile. “Welcome,” he says, “Is this your first visit here?” The showroom is an exhibition focusing on the present; this is where Tallinn brings cyberspace to life. In one of the rooms, which is as cozy as a living room, five rows of seats face a large screen. Various objects are scattered around the room: a small bicycle, plants growing under artificial light, a model depicting a digital parking system in miniature form. A small, grey box with rollers turns out to be a robot being used to test a parcel delivery service in Tallinn. During the EU Digital Summit in September 2017, these robots delivered candy to the heads of state attending. Federico Plantera gives us an extensive lecture on e-services such as a digital ID card, electronic patient file, online voting, digital citizenship, and tax returns at the click of a mouse. What is still science fiction elsewhere is already science fact here. The 24-year-old Italian arrived in Tallinn as an Erasmus student and never looked back. “There is an incredible feeling of community here. Hierarchies are very flat or don’t exist at all.” Whoever wants to do something just does it.

“Everything new created here is designed to be digital. And if it can’t be digitalized, it simply isn’t done.”

The e-Estonia showroom is designed to get political decision makers, managers, investors and the international media excited about e-Estonia and establish connections with leading IT service providers. To date, the information center has welcomed 45,000 visitors from 130 countries.

Project manager Indrek Õnnik works in the e-Estonia showroom, the city’s digital nerve center. The native Estonian gives talks there about paperless administration, online services and life in a digital city.

Developed by Estonians Ahti Heinla, Priit Kasesalu and Jaan Tallinn in 2003, instant messaging service Skype is one of the country’s digital success stories.

In another room, we meet Indrek Õnnik, the information center’s project manager. He swipes across the screen of his smartphone, logs in using his mobile phone number, clicks twice more, and a completed form appears: his digital tax return. Review, confirm, done. “It takes exactly two minutes,” says Õnnik with a smile and holds a small plastic card in his hand like a trophy. The ID card is the symbol of Estonia’s digital society. Estonians use it to pay for groceries and collect loyalty points; it functions as vehicle documentation, driver’s license and digital signature. Just for fun, Õnnik shows us how he can sell his car by smartphone: “All of the data such as the initial registration, odometer reading and inspections are stored online under the digital ID. That information is compiled on the eesti.ee Internet portal, where all the buyer has to do is submit an ID and confirmation, and the car is sold.” Õnnik can also visit the portal to have a prescription for medicine issued. He just has to call his regular physician, who checks his digital patient file and issues a prescription—also digital, of course. At home, Õnnik can use the ID card any time to see who has accessed his health data and when. “There are only three things you can’t do online,” says Õnnik with a broad grin: “Get married, get divorced and buy a piece of property.”

e-Estonia’s showroom is located in the Ülemiste neighborhood, the city’s digital heart. The quarter possesses cult status as the place where Skype was largely programmed. To date, this is said to have generated over 100 spin-offs. It’s lunchtime and people stream out of their offices, returning with sandwiches and salads. During the Digital Summit, two autonomously driven buses ran not far from here. Within just a few months, a system had been developed to transport the Summit’s many guests from the ferry terminal to the city center.

For Professor Robert Krimmer, this example highlights a key trait in Estonia’s population: “There is no fear of digital applications. People here always try to see the opportunities. It means everything new here is always designed and made to be digital. If it can’t be digitalized, it simply isn’t done.” The native Austrian has been living in Tallinn for several years and teaches e-Governance at the University of Technology. He describes Tallinn as “a completely normal city with a digital option.” For Krimmer, the reason why this city’s residents so unanimously and systematically pursue digitalization is the country’s size: “Estonia is a very small country, and people here have always been closely interconnected. Everyone knows everyone.” He compares digitalization’s standing with that of Mozart in his homeland: “All Estonians identify with the country’s digitalization efforts.” Another observation that he attributes to digitalization is speed. “The pace of society has become lightning fast. You have little chance of making plans with an Estonian two weeks ahead of time, because so much can happen in the interim.” One of Krimmer’s fields of research is e-voting. Estonians have been voting online since 2005. How that works is demonstrated in a YouTube video by Taavi Roivas, who was Prime Minister in 2015. In an election period, citizens can vote as often as they want—in the end, the only decision that counts is the very last one. Krimmer says that the procedure is firmly established, but voter participation has not grown demonstrably because of this method. “The expectation that this move would boost political participation has not been met to date.”

Estonia is the first country in the world to offer digital citizenship, which enables people across the globe to set up and manage a company independent of location. Since 2014, more than 27,000 individuals from 143 countries have submitted applications.

Digitalization gives people their freedom back.

Robert Krimmer is Professor of E-Governance at the University of Technology. For him, Tallinn is “a completely normal city with a digital option.”

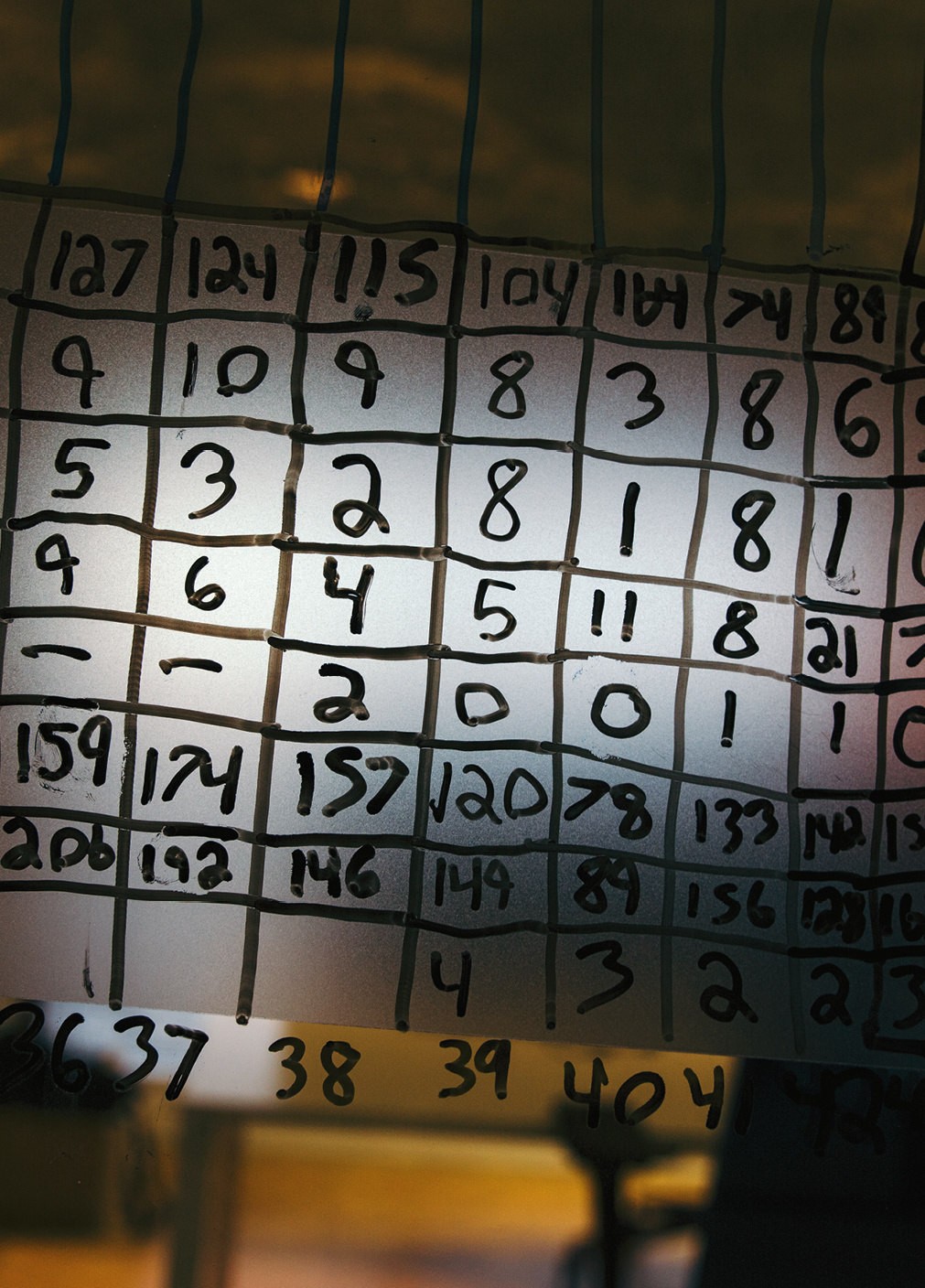

The app reduced student absences by 30 percent in five years. Teachers spend 50 percent less time on administrative work—that makes for two extra teaching days per month.

Valdek Laur and Risto Hansen’s door doesn’t have a bell, and it is locked. Only a phone call or access card allows visitors into the building. A small device on the door beeps, and the door opens. Two friendly men take us into the bright and tidy meeting room with a comfortable couch and two armchairs. Both employees of the Estonian government on the EU Presidency team, Laur and Hansen come across as young inventors who have found their workshop in Tallinn. They instantly start talking about 3D-printed toys and cultured meat. Among other things, they are responsible for autonomous driving applications. “In August, when our auto-nomously driven buses were operating in the city for a month, they were a real magnet. People had fun trying them out.” Laur says it’s important to give people time to get to know new technologies. “Now, the step of integrating self-driving cars into the city will no longer be a major hurdle.” The city’s residents are ready for it. Laur also believes that autonomous driving will make the streets safer. “And it brings people together. Whereas today a bus only goes to rural areas once a day, very soon people will be able to take self-driving cars to a doctor’s appointment or to visit friends. That unifies society.” Estonians readily get to grips with challenges that are considered obstacles elsewhere: “We are currently developing a legal framework for self-driving vehicles. Basically, whoever is in the driver’s seat will be responsible, regardless of whether they are actually at the wheel or letting the car do the driving.” Estonian company Guardtime has also proposed a blockchain-based solution to pinpoint and prevent at an early stage any potential hacking of self-driving and networked cars.

The development of self-driving cars is indicative of Estonians’ mindset when it comes to safety and new technologies. Professor Jarno Limnéll, Estonian expert in cybersecurity at the University of Helsinki, likes to replace the term “safety” with “trust”: “Without a strong basis of trust, you can’t build a digital society.” In other European countries, he often encounters apprehension, whereas in Tallinn everything that can be digitalized is digitalized. “The population is convinced that the government is doing everything necessary to protect the digital infrastructure,” he states. There is also a certain resilience to possible attacks. “That is because, firstly, we inform people about all of the risks. Secondly, we ensure that our citizens have the skills they need to handle digital technologies.” According to Marten Kaevats, Estonia’s mentality is diametrically opposed to that of most other countries: Digital contracts are considered much more secure because, ultimately, signatures on paper can be forged. The city’s psychology also includes feeling comfortable with being a beta tester. “We tolerate errors and disruptions. There are no perfect solutions, only beta versions that we constantly improve,” he says. Always being ready for something new is part of the national psyche.

As Adviser for Digital Solutions, Valdek Laur works on mobility concepts such as autonomously driven cars. A technology enthusiast—he is also a fan of cultured meat and toys made on a homegrown 3D printer.

A log is kept every time the digital attendance and lesson plan book is accessed.

E-embassy: Estonia is setting up the world’s first data embassy in Luxembourg to preserve digital data. The primary aim is to keep sensitive information secure and untouchable.

Even the youngest ones are introduced to the digital world. That’s why virtually every school in Estonia uses the eKool app. CEO Tanel Keres introduced the system into the schools and also uses the digital system for himself as a father to view grades, homework and timetables.

Facts & Figures

Digitalization

And something seen even among the youngest Estonians. Jakob Westholmi Gümnaasium is an old school in the Kassisaba neighborhood. It has heavy floorboards and creaky wooden doors—but a small card reader sparkles at the front entrance. This is where students and teachers register to gain access to the school building. During class, all of the children work on tablets along with schoolbooks and fountain pens. The current topic of study is projected next to the blackboard. Connected via their tablets, the students type in questions that appear on the wall so that they can evaluate and comment on them. Two teachers stand at the front of the classroom: While Kettrud Väisanen teaches social studies, Aet Mikli takes charge of the technology. She continually checks the children’s tablets when she is not sitting up front at the computer steering the presentation. “Wherever we can work with digital systems, we do so,” says the IT specialist. Smartphones are not forbidden, they are integrated into the lessons. “Students should learn how to use the technology for themselves,” she states. The attendance and lesson plan book is digital and can be checked by parents at any time online. eKool developed the corresponding app. The company just moved into a new office in Telliskivi, Tallinn’s creative quarter. Telliskivi is a former industrial complex right in the center of town. This fertile ground for ideas produces ateliers and studios, and an alternative café attracts young people. Tanel Keres, Managing Director of eKool, developed the cloud-based management system for schools along with his team. Teachers use the system to enter grades, homework, absences and the topics of study. Parents can inspect this data, contact teachers and no longer have to call the school to report their child sick. Keres has two school-age children himself. He knows precisely what they are learning at school at any given moment, when they have a test or the next parents’ evening is scheduled—and would receive a message if his children were to not show up for class. The digital attendance and lesson plan book has been used by virtually every school in Estonia since 2002. No one worries about data protection. “Teachers can’t call up their students’ grades in other subjects. Plus, a log is kept every time a profile is accessed,” explains Keres. The app saves teachers work time, making the school day more efficient and transparent.

On the evening before leaving the city, we visit Spanish artist Mar Canet in the Arsi Maja cultural complex. The building appears abandoned and somewhat neglected. Electric cables criss-cross the facade, pipes lead nowhere, an old spotlight clatters in the wind. Studio 312 is bursting with boxes and cabinets, and a rhythmic clicking can be heard. Along with Varvara Guljajeva, Canet formed the artistic duo Varvara & Mar. He is sitting at his desk answering emails. A coworker in the room is taking pictures of tin cans as part of an installation entitled “Data Shop,” symbolizing a store for buying and selling personal data. The cans each contain a storage device with the artists’ personal data from Facebook, Google Takeout, Visa and Mastercard. The label reveals the contents. “Our artistic work explores the relationship between humans and machines,” says Canet. He describes the question of what happens with the data, who collects and uses it, as the “force field of a digital society.” The rhythmic knocking is getting louder. Two metronomes are swinging out of sync. They are attached to a device that recorded the duo’s heartbeats for six months. The artists’ heart rates determine the metronomes’ rhythm. Whenever the pace slows, Mar says: “Now we’re sleeping.”

The capital of cyberspace makes the heart beat faster. Tallinn’s invisible side became tangible for us. You quickly get used to the fact that Wi-Fi can be accessed anywhere in the city thanks to more than 1,000 hot spots. The city is inspiring and fascinating. It has a young, vibrant feel. Marten Kaevats explained to us that a physical presence is still important even in cyberspace—a shared beer, meeting up with friends in the city. His mission is not just to install digital technologies and services, but to build communities around them. According to Kaevats, the preconception that the virtual world is squeezing real social contacts out of everyday life is justified—but also easy to avoid. “Face-to-face meetings are much easier to organize in virtual space.” It’s especially easy to win over like-minded people to an idea and make it happen independently of time and place. Kaevats has long since envisioned the future growing well beyond city boundaries. He calls this concept “hyper local”: “A world in which physical location is irrelevant, because the entire world can be accessed from anywhere.” People might then obtain e-residency in Estonia to start a company, while using the health care system in Switzerland and banking elsewhere. “We will then have to build trust between strangers, potentially from all over the world,” states Kaevats. Tallinn is living proof that digital technologies can do just that.

Further photo credits: Annika Haas